Willie Pep -

Advanced Striking 2.0

In the pantheon of boxing greats, Willie Pep is a name that many fight fans know but few seem well acquainted with. Pep is the perfect example of the early twentieth century boxer: he had almost two hundred and fifty recorded professional fights, a heap more as an amateur, and less than a dozen of them made it onto film. And those dozen reels of Pep only exist because he reached the pinnacle of his sport, managing two featherweight title reigns from 1942 until 1948, and then from 1949 to 1950.

The most famous story about Pep was that he once won a round on the scorecards without throwing a single punch. Ahead of the fight, the old master tipped off his friends on press row to look for the fifth round. The round came and Pep proceeded to feint and juke his opponent into knots, dominating the three minutes, seeming to eat his man alive, with only those select few boxing writers who had been forewarned noticing that Pep never truly hit his opponent. Modern fight historians have since ruined this great story by selfishly researching and proving that it did not happen, but such was the reverence for Pep’s scientific boxing that this story was widely repeated and accepted as gospel while he was an active competitor.

Fig. 1

Pep was a master boxer by any measure. While fight film of many early twentieth century boxers can be disappointing, Pep’s fights demonstrate a remarkably deep bag of tricks. Everything from the masterful jabbing and feinting you would expect, to arm drags and elbow passes to break out of clinches and reverse ring position with the opponent. Despite being a noted non-finisher, Pep could crack respectably with his right uppercut, and he used it in creative ways. In his four matches with noted rough customer, Sandy Saddler, Pep gave as good as he got and showed that he could be as creative with his fouls as he was in every other aspect of boxing.

But the facet of the sweet science where Pep most obviously departed from orthodoxy was in his movement. It is impossible to say that Pep—or any fighter—“invented” anything, but the way that Pep re-examined lateral movement and built his style around it was nothing short of revolutionary. Pep famously said that the downfall of a fighter is “first your legs go, then your reflexes, and then your friends.” There is something revealing in that quote: Pep was not a power puncher, he was not a volume puncher, he was a dancer. His boxing career lived, thrived, and then died with his footwork.

The Athletic Side Step

If we examine the classical side step, it can be performed to the fighter’s left or right though it is most commonly performed to the side of the power hand. In the classical side step the fighter turns his feet in the direction of movement and steps forwards out to the side of the exchange.

Fig. 2

The fighter then turns back to face his opponent from his new position. Figure 3 shows a diagram from Finding the Art. The fighter can cut a substantial angle on his opponent in this way and the side step to counter right hand is a timeless technique.

Fig. 3

To perform the technique to the left, the fighter simply steps out to the side with his lead foot.

Fig. 4

Pep’s revelation was to treat boxing as if it were any other sport. Football, American football, rugby, baseball, cricket, basketball: all involve rapid lateral movement. Sometimes that is performed by turning to run in the direction of the movement, but more often than not it is done with a true side step. The feet are brought to level, then the rule of “outside foot, inside foot” is observed: the athlete steps out with the foot that is nearest to the direction he wishes to travel, extending the distance between his feet, and then his other foot comes up to shorten that distance again. Where the classical side step of boxing is clumsy to string together in sequence, the athletic side step can be repeated rapidly until the fighter gets tired or—in a boxing ring—dizzy.

Fig. 5

While the rule of outside foot, inside foot is almost always followed instinctually by athletes—no one crosses their feet to begin side stepping, after all—there is an additional flexibility to the athletic side step. Once the initial outside step has been taken, the athlete can bring his second foot all the way up to his leading foot to gallop into the next stride and maximize distance covered.

Fig. 6

Athletic side stepping was not common in boxing for the glaringly obvious reason that the feet must be level. The basic footwork of boxing involves short outside step, inside step side movements from the stance, but with the feet staggered the distance travelled on the side step is not significant. The classical side step developed to cut a large angle, while maintaining a strong stance from which to hit, get hit, and defend. But in the modern era, whether it is a great ring general or a great ring cutter, both will bring their feet close to level at points to facilitate rapid lateral movement.

By the time of Pep’s arrival to prizefighting, there had been plenty of fighters using the athletic side step to reposition themselves and avoid exchanges—Gene Tunney and Tony Canzoneri stand out—but none had incorporated it into their boxing in the same way Pep was able to. For every instance where Pep was frantically working to escape the pressure of a Sandy Saddler, there were a dozen more where his lateral movement set traps and enabled his own offence. While Pep insisted throughout his life that “he who gets hit and runs away, lives to fight another day”, his style was not so much “hit and run” as “run to hit.”

The Pep Step

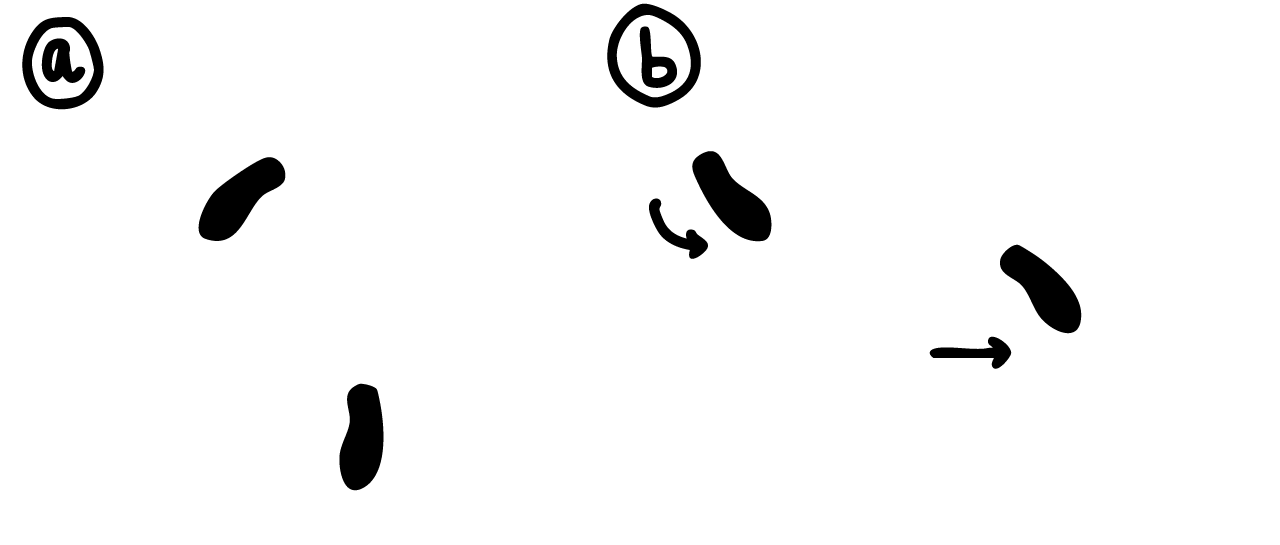

The technique—or perhaps tactic—that scored Pep many of his best blows was one I have come to call The Pep Step. Figure 7 shows the footwork. Abandoning his stance, Pep brings his feet level and starts circling to his left (a), (b), (c). As his opponent steps across to cut him off (d), Pep kicks his left foot out and turns his feet back to face his opponent, ready to leap in with a southpaw left straight.

Fig. 7

You will notice that Pep brings his feet together in frame (c). While a cardinal sin in traditional boxing, this allows him to plant his right foot into the mat, and kick his left foot out behind him to establish the southpaw stance. This “bumping” of the feet together set up many of Pep’s direction changes.

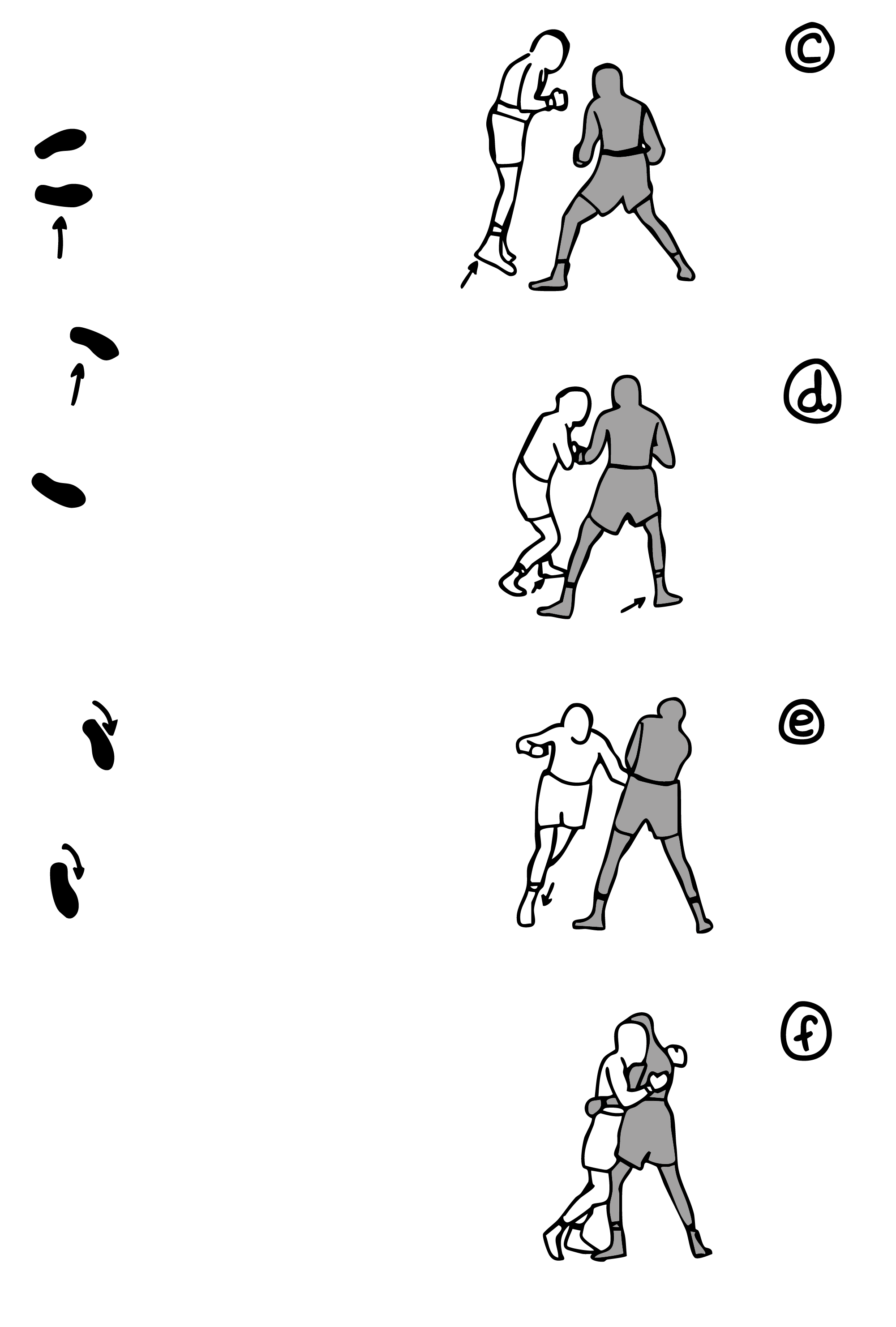

Figure 8 shows an example of Pep side stepping just as his opponent commits with a jab (b), (c). Pep rapidly turns his feet to face the opponent and drops his weight (d), ready to spring in with his southpaw left straight (e).

Fig. 8

The Pep Step alone could be considered a primer on the rules of movement in the pugilistic art. It demonstrates that when the feet are level, lateral movement is more free and versatile. Yet to hit with any venom, the fighter must point his feet at the target and get his feet staggered again so that he has a means of transferring weight.

Figure 9 shows an example from one of his fights with Sandy Saddler where Pep is circling along the ropes. In this instance, Pep initiates his lateral motion with a classical side step—turning his feet towards the direction that he is circling (b).

Fig. 9

Pep did not eschew classical side steps completely, because while the athletic side step provides more mobility, the classical side step has a couple of advantages of its own. It takes the fighter’s head further away from the exchange, it keeps the fighter down behind one shoulder, and it puts his other forearm in the path of the expected swing that would cut him off. If you are expecting to absorb a blow, the classical side step is usually the better option.

As Saddler follows Pep to the right, Pep bumps his feet together (c), and turns to face Saddler as he kicks his left foot out behind him into a southpaw stance (d), (e), returning with a powerful left hand to the body. Pep immediately ties up to limit the exchange (f).

Fig. 10

Direction Changes and Psychology

The science of ringcraft can be seen at its zenith in those old fight films when Willie Pep is about to be cornered. It is then that the dancing master shows his wiles. Pep had a hundred little tricks but the basic element that made him so difficult to trap was that athletic side step. By bringing his feet back to level, Pep could sidestep in a way that not only enabled faster circling of the ring, but rapid changing of directions as well.

Pep could step his left foot out to the side, lean onto it, halt himself, and rebound back in the other direction. The simple juke of American football, or soccer, or rugby. The beauty of the direction change is that it punishes the competent ring cutter. A good ring cutter like Sandy Saddler would not follow Pep around the ring but rather step across to interrupt his circling. It was as the opponent committed to cutting him off that Pep would change direction and slide out the other side.

Fig. 11

And within the direction change there is a simplicity that matches rock-paper-scissors, but a complexity that goes deep into anticipation of the opponent’s expectation. Pep could change directions once, twice, thrice, or pause as if to change directions only to continue circling the same way.

An additional advantage of using the athletic side step with his feet level was that Pep’s head was free to move from side to side, and he was able to change levels at both the knees and waist. Think of how easy it is for a wrestler to get his head low with his feet level. Escape was not always necessary for Pep, if he ducked low and the opponent came too close he could just hug their waist and get a break from the referee. The opponent was left walking a tightrope of trying to hit him as best they could when they got the chance along the ropes, but not miss and give him an easy tie up.

Saddler found success against Pep, and won three of their four bouts, but a look at the record does not do justice to the difficulty of the fights. The footage of the one Pep - Saddler bout that we do have is a back-and-forth battle fought at a torrid pace. Saddler was able to slow Pep down and hold him in one spot by attacking the body as Pep circled along the ropes—because these blows are impossible to duck—and by holding and hitting whenever he could.

Even when his footwork was falling short, Pep began loading up his uppercut and tried to at least take a few of Saddler’s teeth home with him if he was going to lose. All of Saddler’s offensive ringcraft—some of the best we have ever seen—only achieved the goal of getting him into a tear up with Willie Pep, it didn’t make Pep a useless fighter without his legs.

Pep’s lasting legacy is a curious question, because I am not sure that fighters using lateral movement with their feet level even know that Pep was among the first to do it. Around the same time as Pep, Sugar Ray Robinson was having tremendous success dancing around the ring canvas, and his celebrity massively overshadowed Pep’s. Though he tended to stay a lot closer to his textbook boxing stance than Pep did. Whatever the case, the classical side step has largely fallen out of favor, particularly along the ropes. When a modern fighter hits the boundary, he squares his feet and—if he’s any good—he starts cycling through direction changes as Pep did.