Arman Tsarukyan vs

Beneil Dariush

There is only so much you can say about a fight that lasted a minute and ended on the first real exchange. The correct thing to say is “wow”, and the result surely marked Arman Tsarukyan’s ascent from the lightweight shark tank into the “name” contenders. This is particularly gratifying because the trio of Dustin Poirier, Michael Chandler and—to a lesser extent—Justin Gaethje have been sitting on their top ten rankings for a long time without offering an opportunity to the group of impressive contenders trying to scramble their way up the ladder.

The knockout came off an overhand right into a double collar tie. Figure 1 shows the sequence. Tsarukyan jabs in (a), gets outside foot position and throws a long right hook behind Beneil Dariush’s guard (b). Dariush is covering up and actually ducks in as Tsarukyan grabs the double collar tie (c). Tsarukyan throws the knee and Dariush stands up in time to move with the blow (d) (e), but is met with a short right hand off the same side that sends him to the mat.

Fig. 1

To most fans this would simply be impressive, but to anyone who heard last week’s Boicast it had an added layer of hilarity. With a significant height advantage and a good double collar tie, it was Dariush I was hoping to see swing his way into this position and threaten the knees. It is made even dafter by the fact that Dariush has used this exact clinch entry on numerous fighters and I specifically referenced this overhand to double collar tie from the Barboza fight while musing over what Dariush should be doing in this bout.

Fig. 2

While it was overshadowed by a criminally bad stoppage, Jailin Turner’s performance against Bobby Green was one of the most measured dismantlings of the year. Green provides a number of unique challenges, and Turner made them all count for naught while taking Green apart on the feet, in the area Green feels most at home.

The most significant part of Turner’s performance was his ability to use the jab to draw out Green’s slips and counters. Figure 3 is a perfect example from the opening minute of the fight.

Turner jabs and Green pulls (b), Turner partially recoils his lead hand (c), and pumps a second jab which sees Green slip to the elbow side (d). Green returns with a southpaw right hook but Turner—being taller, longer, and carefully staying over his feet—easily leans out of range (e). Green has thrown himself out of position and Turner jabs in to see if he can capitalize before holding off on the left hand and letting Green move back to range.

Fig. 3

Throughout the fight Turner threw slappy, uncommitted low kicks to knock Green’s lead foot out when he stood in his longer stance. Turner scored blows on Green when his feet came to level—as he feinted kicks and marched forwards after a retreating Turner. And Turner made good use of high kicks to attempt to punish Green for his slips and leans.

Another important look in the fight was Jailin Turner’s dart. Figure 4 shows this in action. Turner jabs in (b), then throws his southpaw left straight and Green slips deep to the elbow side (c). Turner’s trailing left foot skips up to replace his right foot (d) which is kicked out behind Turner to put him in an orthodox stance, well past Green’s lead foot and shoulder (e).

Fig. 4

A dart can be a very committed strike—as when Eddie Alvarez leapt into his—but Turner managed to use it to put distance between himself and Green when Green got close to a good counterpunching position.

Both the double jab and the dart were a feature of the finishing sequence, shown in Figure 5. Turner double jabs in and Green slips deep to the outside of the second jab again (d). This time Turner goes to him with the right hand and hits him in the slip (e), darting off and switching from orthodox to southpaw (f).

Fig. 5

Due to Islam Makhachev and Arman Tsarukyan we have been talking a lot about the double collar tie as a means to punish a dipping opponent in the last couple of months. The boxing method of punishing the slip has traditionally been the uppercut but you can just as easily take your traditional punches to the slip. Just a few months ago, Ikram Aliskerov did this same thing to Phil Hawes. If a fighter is showing the same slip a few times—and you have drawn that out of him with your jabs or feints—you should change the path of your punch and catch him in the slip.

Figure 6 shows an alternate angle of Turner nailing Green in the slip. Clearly his right straight isn’t as pretty as if he were throwing it directly in front of his own centreline as he would in shadowboxing or on the mitts, but those prettier punches wouldn’t have found Green. As a bonus, Turner uses his shoulder to take the brunt of Green’s left hook, and darts off into southpaw. By doing this he breaks the line of attack and makes it difficult for Green to follow him out of the exchange (had he not shaken up Green’s whole world with this punch). A second later he threw a one-two and hit Green in the exact same place on the same slip once again for the knockdown.

Fig. 6

Deiveson Figueiredo’s bantamweight debut was an impressive one, but was aided enormously by Rob Font seemingly having an identity crisis. While Font’s comeback against Adrian Yanez was important for his career and won him many fans, it apparently taught him the wrong lesson as he simply threw his right hand at Yanez’s chin until Yanez collapsed. Since the Marlon Vera fight his bodywork and low kicking has largely dried up. Every low kick and body shot he threw against Figueiredo found the mark and visibly affected Figueiredo, and yet threw less than five of each.

Even the Font jab, which has always been well regarded, was underused in this match. He flicked it out a couple of times in the opening round and Figueiredo found a good cross counter over the top. That was all it took to get Font to abandon the weapon for most of the fight. Instead Font faked a jab that seldom ever actually arrived, and relied on head hunting with hands and collar tie hockey punches.

Figure 7 shows a typical example. Font holds a high guard, steps in deep and feints a jab without opening up (b). He immediately ducks an expected return (c) and grabs Figueiredo’s head with a collar tie (d) in order to swing a right uppercut (e). He follows Figueiredo out of the exchange (f) and is immediately blasted with an uppercut as he tries the same dip and reach for a collar tie again (g).

Fig. 7

Figure 8 shows Figueiredo using the uppercut again to try and time Font’s feint. This works out as an inside slip uppercut: a powerful and risky counterpunch that you don’t see an awful lot.

Fig. 8

Khamzat Chimaev knocked out the aforementioned Ikram Aliskerov with it, and Gentleman Jim Corbett wrote that it was his favourite counter. Newspapers report that it was Corbett’s uppercut that made Bob Fitzsimmons bite his own tongue in half, so there’s a decent chance it was this counter.

Fig. 9

Notice in Figure 8, Figueiredo immediately digs the underhook and turns to face Font.

The Figueiredo - Font fight is another classic example of a fighter being elevated by his opponent’s performance. Just as Ronda Rousey looked like an unstoppable ring cutter until she met someone who knew to circle left and right, Figueiredo looked like the master ring general because Font simply ran on a straight line at wherever Figgy had been standing when he decided to attack.

Fig. 10

With that being said, Figueiredo’s wrestling looked terrific. This was a man that only really had a double leg and an inside trip from the over under. In the course of this fight he hit a trap hook dump, a single leg which he completed by running the pipe, and a foot sweep that flowed into a knee tap.

On the other end of that Font, who had some trouble on the mat against Cory Sandhagen in his last fight, looked cool and composed on the mat. Figueiredo could get Font down and Font would use his butterfly hooks or a Leite style half guard to build back upto the feet meeting no real resistance. Font’s bottom game only failed him in the third round when he had been battered by big punches and got mounted.

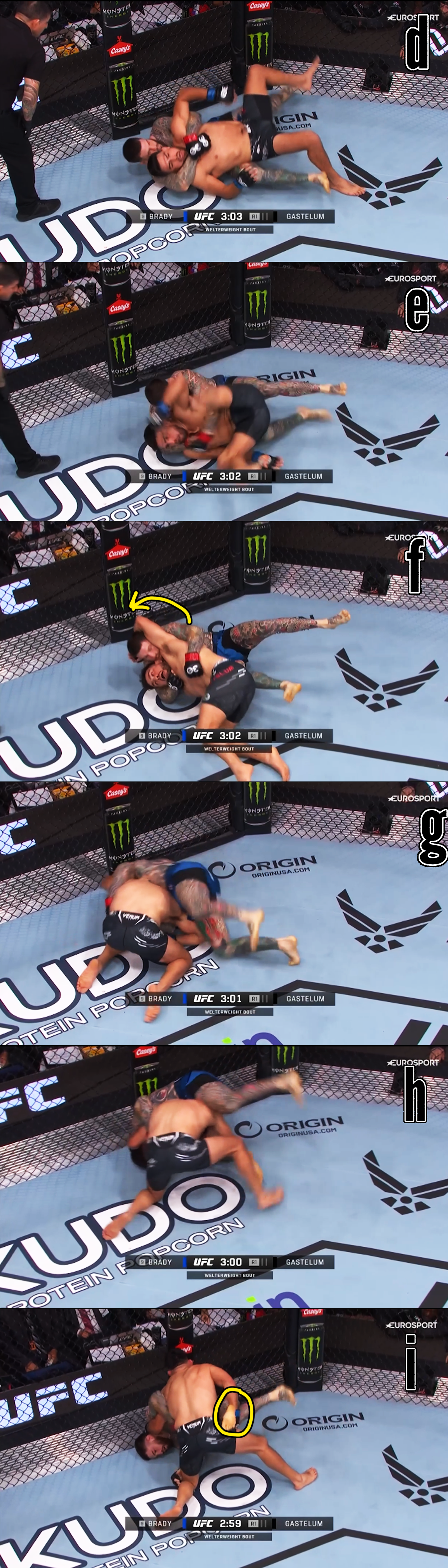

On the subject of the ground game, Sean Brady dominated Kelvin Gastelum in their welterweight meeting, but Gastelum demonstrated one unusual look worth touching on. To begin Figure 11 shows Gastelum in a body triangle (a), he frees his left leg by lifting it off of Brady’s left foot and scooping underneath it (b). Brady unlocks his legs to try and reapply a body triangle (c).

Fig. 11

Gastelum rolls to the other side (d) and hops over Brady’s right hook (e). As he turns to his knees he reaches up over his head and wraps his arm over Brady’s head (f). This means that he can peel Brady off him as he turns up to his knees (g), (h). As he comes up on top, Gastelum grabs and elevates Brady’s right foot to prevent him from scrambling up (i).

Fig. 12

In wrestling you will sometimes hear this technique being called a head catch Gizoni, apparently after Tony Gizoni, but in wrestling it is performed off a short sit rather than having the opponent backpacking you.

Fig. 13

Ray F. Carson was a coach who wrote about trends in wrestling through the sixties and seventies and when he wrote Counter Control in Wrestling, the short sit out was just coming to prominence. He details this head catch Gizoni as the most popular “move” out of it at the time. Carson was not sold on the short sit back then but it has proven invaluable in wrestling, grappling and MMA in the years since.

A final note should be made for the quality scrap between Clay Guida and Joaquin Silva. There were numerous excellent uses of the inside reach made by Guida, and the lead hand uppercut as a counter to the level change by Silva. But the one moment I want to shine a light on was the high kick Silva scored in the last round. Figure 14 cannot do it justice but gives the gist.

Silva retracts his left foot and advances his right in a switch step (b). He throws his left hip forward as if to switch kick (c), but stops (d) and allows Guida to react to the kick and then begin moving back to his guard (e). As Guida begins to recover his position Silva completes the kick for real (f), (g) and scores clean. Another terrific example of both feinting and waiting a beat in the middle of a technique.

Fig. 14