Roberto Duran: Bridging the Range Gap

- Advanced Striking 2.0

“He wants to catch Leonard with that right hand, and to do it he has to beat one of the greatest left hands in the business.”

— Ferdie Pacheco on commentary during Leonard vs Duran I

Roberto Duran is remembered for his role in the era of Four Kings. As the heavyweight division slipped from the spotlight, Sugar Ray Leonard, Tommy Hearns, Marvin Hagler and Roberto Duran took centre stage in a blistering series of fights. When looking down the records it is clear that Leonard scored wins over each of the other “kings”, and Duran was the only one to suffer losses to all of them. But the black and white of a record hides the significance of the bouts and of Duran himself.

Fig. 1

The earth-shattering information that most fans only discover after diving deeper into the history of boxing is that Duran was already a relic. The Four Kings met at welterweight and middleweight. Duran had already spent twelve years carving out perhaps the greatest lightweight career of all time before he gained weight in order to hand Sugar Ray Leonard his first loss. Duran was an early seventies champion who became a star in the 1980s. Everything that Duran is remembered for in modern boxing—going from lightweight to light heavyweight, beating Iran Barkley while looking 30 pounds smaller on the night, winning a middleweight title at five-foot-six—took place in the twilight of his fighting career.

In this writer’s mind, Roberto Duran is the textbook. There is much to be gleaned from his lightweight career, and his mastery of infighting is almost unparalleled. But in this study we will focus on an aspect of Duran’s game that had to be honed later in his career and brought him back into competitive fights with bigger, younger opposition, long after his prime.

Education of a Jab

The combination of moving up in weight and getting older necessitated a change in Duran. Where before his punch was numbing, it was now just decent. To get the better of bigger, stronger, more durable fighters, Duran was forced to create the openings for heavier blows and commit to them. This led to a number of developments in his technique and tactics.

As a lightweight Duran had been able to do just about everything. He was known for his thunderous power and mauling infighting, but if he wanted to stand back and jab he was an accomplished enough technician that he could. As his opponents became noticeably bigger and longer than him, Duran prioritized pushing to the inside. His early welterweight run involved a lot of charging opponents down and this was most obvious in the first fight against Sugar Ray Leonard, whom Duran repeatedly bull rushed to the ropes.

The second Ray Leonard fight and losses to Wilfred Benitez and Kirkland Laing demonstrated the trouble Duran was going to have against these bigger men if he got stuck on the outside at jabbing range. The loss to Laing was a massive upset, which was offset somewhat by Duran’s reputation for getting horribly out of shape between bouts, but it most clearly demonstrated that charging down bigger men was a tiring and difficult task. Laing towered over Duran and had a low hands, movement heavy style that led to Duran tripping over himself with lunging rights, and bruising his pride more than his face.

Duran’s development over the next few years saw a recalibration of his offence. From his fight with Jimmy Batten in 1982 until the end of his storied career, Duran seemed to rely more heavily on interplay between his own jab and his infighting. This meant that even when Duran gave up eight inches of reach and eight inches of height to Iran Barkley, Duran was using the jab just as frequently and effectively as Barkley was using his own.

Duran’s success in the heavier divisions was largely built on a relatively simple tactic known as “jab and dip.” The gist is that the fighter throws his jab, without a care in the world whether it lands of not, and moves his head immediately as he retracts that jab. The idea is that any world class boxer is not going to let you throw hands without trying to throw back, so as soon as your jab returns, you need to be in a different place to where you started.

The genius of it is that when the opponent punches—or most likely jabs—back, they open their elbows away from their body. This meant that if Duran jabbed and immediately changed level and moved his head offline, he could get right up next to them and fire one or two good body shots on their open flanks. Duran’s ability to stick to his opponent without holding or being held also meant that he could force his way into a period of infighting from any successful entry.

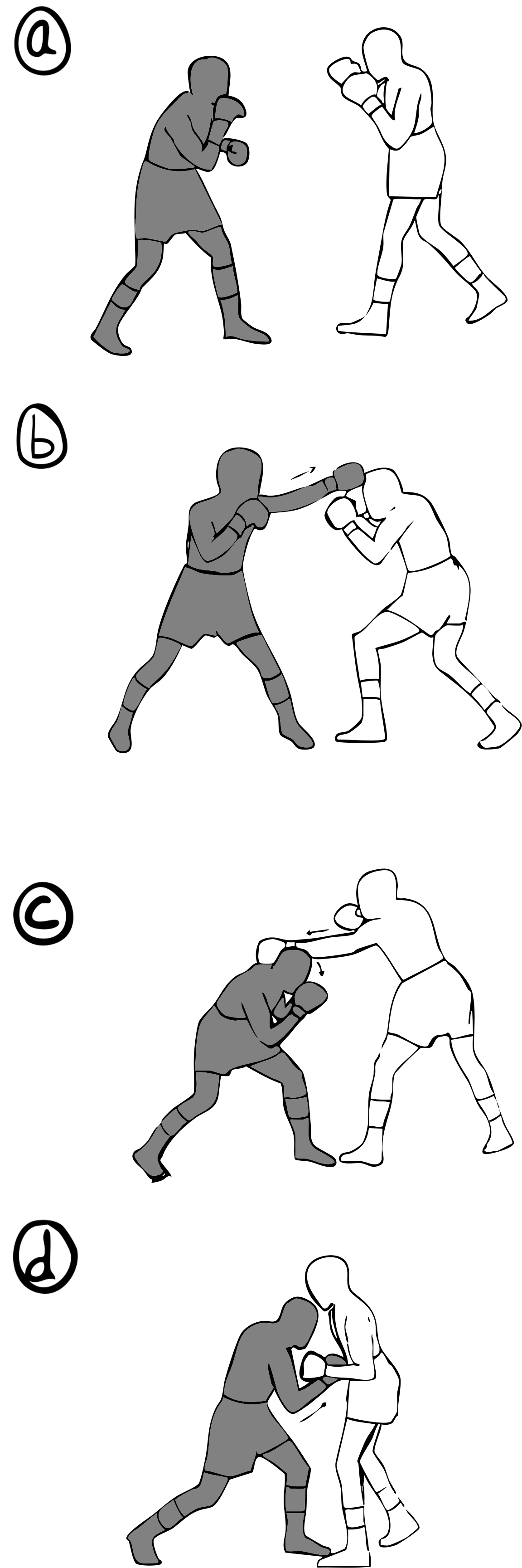

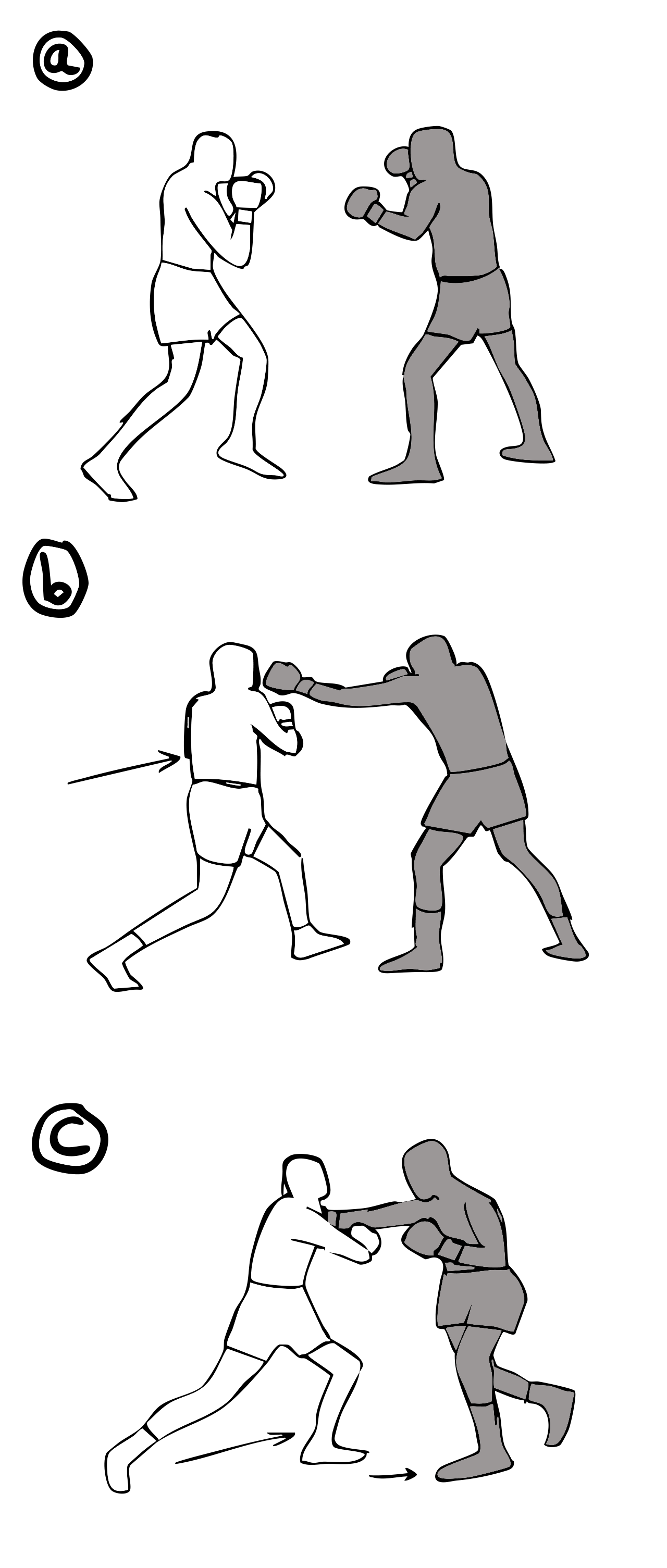

At its most basic, the jab and dip works in two directions. Figure 2 shows how Duran would jab, step in and change levels with his head to his left, and then come back with the left hook to the body or head.

Fig. 2

Figure 3 shows how Duran could perform the jab and dip with his head to the right, returning with the wide right or uppercut to the body, or the outside slip counter.

Fig. 3

These are the most fundamental applications of the jab and dip, but Duran might just as easily slip to his left and throw his right hand, or slip to his right and throw his left hand. This resulted in impure, partial punches, but served to surprise the opponent.

The jab-and-dip is somewhat similar to the now seldom seen serve-and-volley in tennis. Duran served up the jab expecting the counter, but was already rushing into position to attack that return. While the jab and dip is a single tactic, it perfectly embodied Duran’s larger strategy of getting the opponent into a jabbing battle first, in order to more predictably open the route to the inside.

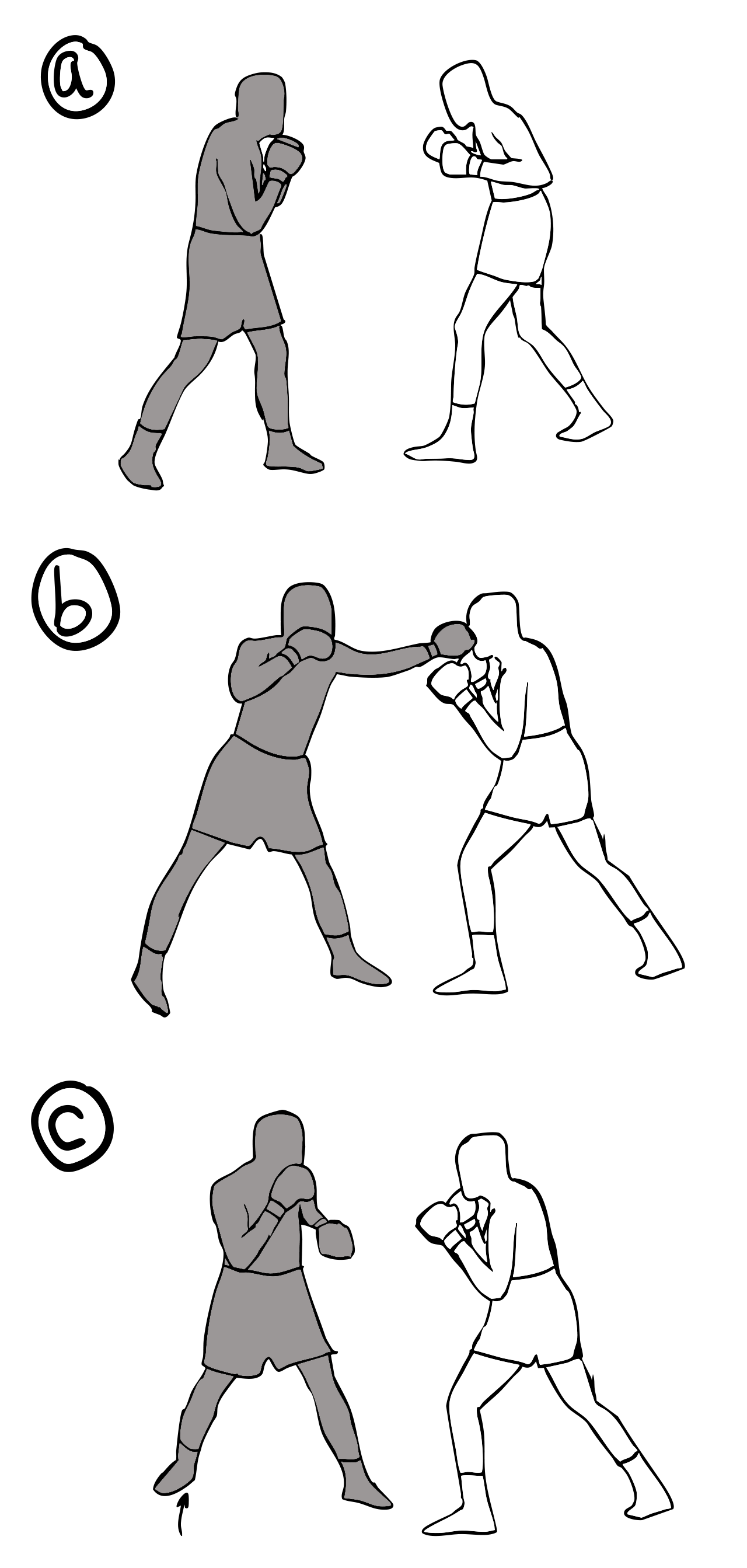

This use of the jabbing battle to enter was not new to Duran, but his later career showed a renewed focus on the concept. A great example from Duran’s lightweight run came against Hiroshi Kobayashi, shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4

In the final round of the fight, Duran began jabbing and circling with Kobayashi, and not always getting the best of it. Finally he jabbed (b), circled (c), set his feet again (d), and slipped (e). This was because after he was done circling, Kobayashi snatched the soonest opportunity to throw his own jab. Duran slipped inside and unloaded with both hands (f), stunning Kobayashi and following up to score the knockout.

Duran’s jab improved as he matured but that was a bonus. The key to the whole strategy was that he jabbed enough to make the opponent engage him in a jabbing battle. Standing on the outside and trying to react to boxing’s fastest punch, slip it, and rush in is exhausting. When a fighter engages in the jabbing battle in good faith, his opponent’s jabs are much easier to read or even encourage at the right times, opening the path to the inside without all the rushing around and panicking. The circling jab was a key aspect of that. Duran opened almost every round of his later career by circling to his left and pumping out the jab.

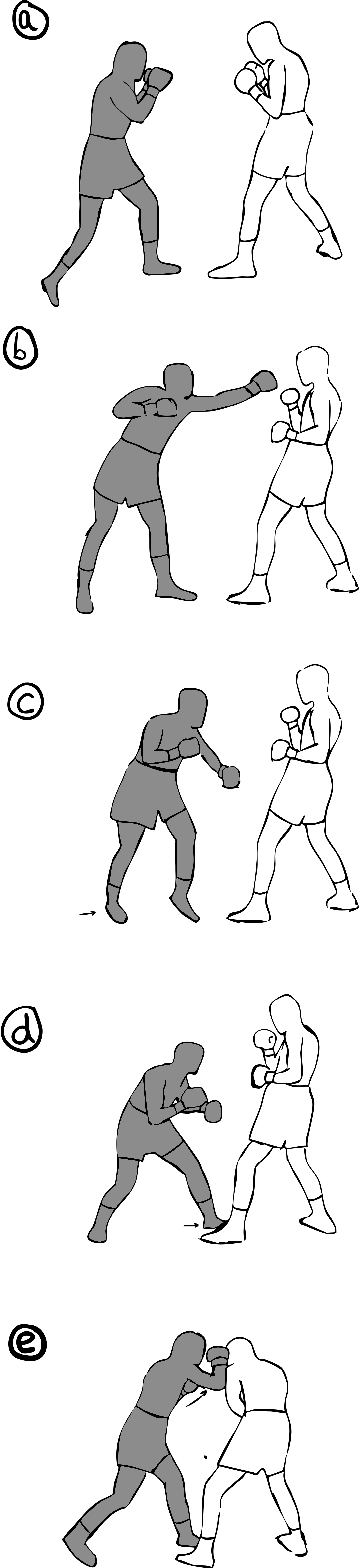

Duran did this by crossing his right foot behind his left, as in Figure 5. This stands in sharp contrast to the way that Sugar Ray Leonard jabbed to his left, by taking a big diagonal step with his lead foot and then swinging his right foot back into stance behind it—never crossing his feet.

Fig. 5

Crossing the feet on the jab is a bad idea in combat sports where it is legal to attack an opponent’s balance or legs. But in boxing this is one of the few practical occasions to cross the feet. By moving in this way the fighter drifts slightly off the opponent’s line of attack, and brings his body onto knife edge behind his lead shoulder—frame (c). The idea is that you poke out the jab and immediately take away most of the opponent’s targets while you step around and then you both reset position.

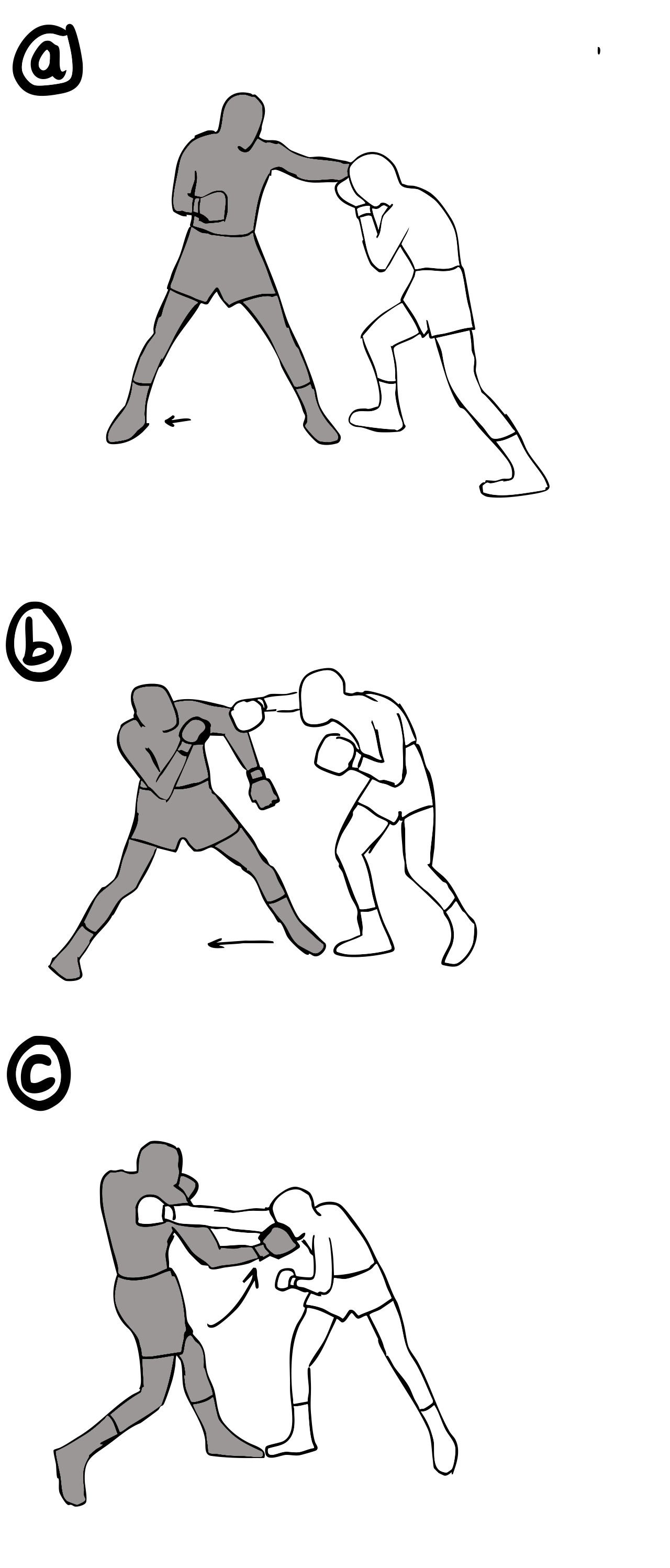

When Duran flicked the jab and performed his little cross step, his opponent would often throw the right hand across the top of the jab on the return. Figure 6 shows an instance from the Barkley fight.

Fig. 6

By blading his body behind his lead shoulder, Duran could shoulder roll the right hand (c), and then return at his squared up opponent. But being Duran, he would seldom pitch the straight right from the textbooks, but would rather swing a right hand at the body. In Duran’s fight with Robbie Sims, Gil Clancy remarked that this was “a typical Duran move. I don’t know anyone else I’ve ever seen make that move.”

When Duran fought Leonard the first time, he spent the early part of the fight almost sprinting to the inside, but pleasantly surprised even himself during the outfight. Duran’s cross stepping jab annoyed Leonard by offering him few good counter shots. Figure 7 shows the moment that Duran stunned Leonard off the cross stepping jab.

Fig. 7

It can be difficult to follow up having crossed your feet (c), but Duran hopped his lead foot out wide and deep, down the outside of Leonard’s right shoulder (d). Duran came in with a right straight and a left hook while standing almost on top of Leonard (e), (f).

Commitment to mastering the jab and dip elevated Duran’s performance because it made great use of existing elements of his game. He was already a terrific body hitter and infighter. But he also had a beautiful outside slip: perhaps the best of anyone to ever lace up gloves. The outside slip is taking the head to the outside of the opponent’s jab and letting it brush past your left ear. Most fighters can do it, and many are great at it, but Duran was the best at returning off it. From Sugar Ray Leonard to Iran Barkley, most of Duran’s biggest connections came off the outside slip and a counter right hand, high on the temple.

To throw the right hand with power off the outside slip, the fighter needs to rebound off his right foot. Many fighters use their outside slip as an evasion and stand in place to do it. To crack like Duran, it was necessary to time a slight step of the right foot to get it in place to throw him back into the fray after he had avoided the jab.

Nowadays it is far more common to see a pull counter to land the long right hand over the opponent’s jab, but when Duran was giving up so much height and reach in many of his later fights this would not have been a realistic option.

It is difficult to deny that Roberto Duran’s feet slowed down in a dramatic way after he left lightweight. Many of his great later showings involved tricking the opponent into standing and fighting rather than dancing around him. Yet when studying Duran’s fights, it is surprising to see just how busy his feet were.

The jab and dip, and the outside slip, reveal this trickiness of Duran’s footwork. Because he wanted to rebound off his right foot, it was common for Duran to jab and then dip backwards into his stance, over his right foot. Because of this, the outside slip worked best when the opponent was moving towards Duran.

But Duran also used the outside slip to get to the inside. When he did that, he had to move forwards, while leaning his weight over his back foot. And to do that he had to perform extra steps in the same amount of time.

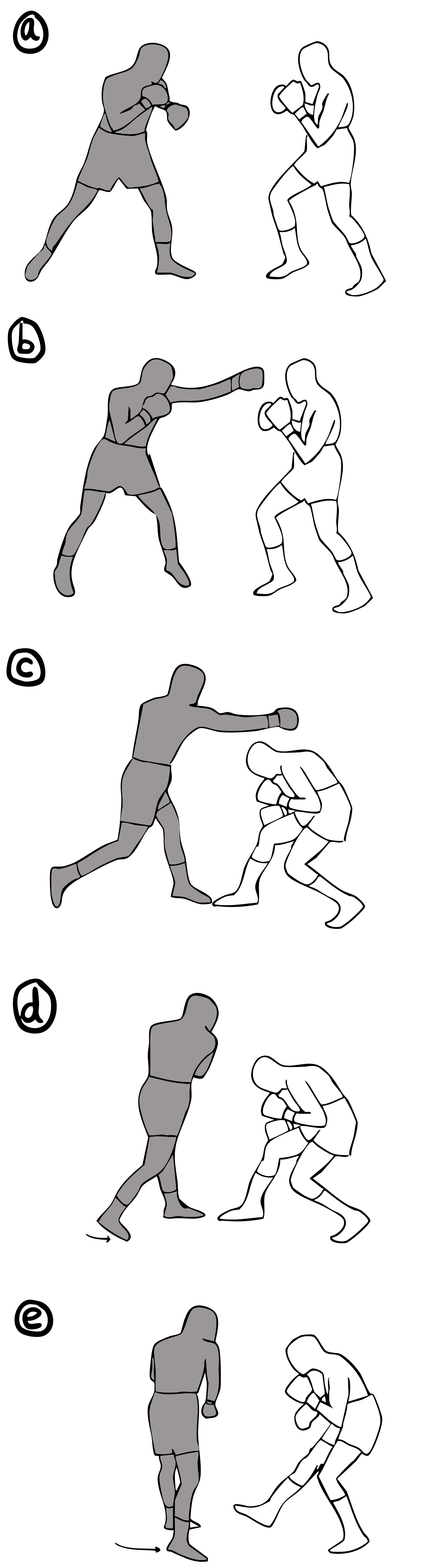

Fig. 8

Figure 8 shows an instance from the Robbie Sims fight. Duran jabs (b), but gallops his right foot up underneath his centre of gravity (c), allowing him to step forward with his left foot while moving his head out over his right leg (d).

In this instance, Sims did not open the door to his body by jabbing back, so Duran came up out of his crouch with a right hand of his own (e). Coming up with a long right hand is a great answer to the opponent shelling up in the face of the jab-and-dip, and was a favourite of Aaron Pryor as well.

Rotation on the Right Hand

“I always used to tell Duran that his fights were won during training and he would tell me that it didn’t matter because he had a right hand like Ingemar Johannsen.”

- Carlos Eleta, Duran’s manager

Boxing at its most basic can be considered the art of landing the right hand. The jab was invented to ease in the right hand. The majority of the population are right handed, stand with their right hand in the back of their stance, and can throw it much harder than their left.

But when faced with an opponent in the same stance, looking to do the same thing, the line of the lead shoulder and the movement of the opponent’s head and guard make landing good right hands from out in the open one of the most difficult tasks in boxing.

Duran was an anomaly: landing more simple one-twos on elite competition than almost any fighter not known for their reach and height advantage. Lennox Lewis landing an enormous number of simple one-twos when his opponent can neither reach him, nor stay out of his range, is not nearly as impressive as the five-foot-six Duran scoring clean one-twos on the chin of taller, rangier boxers.

Much of this was down to his work with the jab-and-dip. Once opponents began shelling up off his jab and not exposing their midsection and a path in, Duran could shellack them with the one-two without fear of eating a counter.

More than the tactics, the mechanics of Duran’s right hand are worth examining. When Duran threw his right hand long, he often shifted in with it in a manner so unique that you could recognize it in silhouette.

As boxing coaches often say, the body is a pivoting machine and that rotation creates the power for blows. But there are a number of movements you can perform to get your hips and shoulders turning. When Duran threw his right hand, it was as though he had an iron rod keeping his knees apart, but he would pivot around his left foot and swing his whole stance around. He moved like a gate being slammed shut.

In many instances, Duran could be seen pitching the right hand as his opponent moved out of the way, and seemed horribly overextended.

Fig. 9

When Manny Pacquiao fought Tim Bradley, Bradley exploited Pacquiao’s tendency to overcommit his weight in a similar way when he threw his southpaw left hand.

But when Duran landed, he carried his full body weight with him, and often slammed straight into the opponent in a chest-to-chest clinch, or into the infight. He was perhaps the best proponent of “punch-and-clutch” in boxing. In the first Leonard fight, Duran repeatedly threw the right hand, shifted in, underhooked Leonard with his right arm, and pushed Leonard onto the ropes. Against Davey Moore, Duran did the same thing and then stayed pressed tight to the referee as the clinch was broken, so that he could begin infighting along the ropes with no preamble.

Though it sometimes led to eating counters while off balance, the falling-in right hand was a technique that Duran used and not a calcified bad habit in his muscle memory. He regularly threw right straights without shifting, and against Marvin Hagler—after failing on this shifting right a few times—he began flicking out a one-two-one to reset his guard and pop Hagler for free as he tried to duck in under the right hand.

A different mechanic that Duran used was an intercepting right while shortening his stance. As the opponent stepped in, Duran rotated his hips and threw his right hand, as he drew his lead foot back to give ground. This can never be as powerful as moving the bodyweight into the blow, but it is a way in which the shoulders can be whirled with decent force while retreating.

Fig. 10

This technique was at its best against charging opponents, and Duran used it three times to knock down and eventually finish Jimmy Robertson in 1973. Two other scenarios in which Duran used this technique were against southpaws and with his own back to the ropes. He used it successfully against Marvin Hagler, Robbie Sims and Iran Barkley.

Figure 11 shows a curious variation of this technique that Duran used against Juan Medina, a month after knocking out Robertson. Duran spent several rounds getting the read to step out to his right, then pulled his left foot, hip, and shoulder back to power a colossal right uppercut. In round seven, Duran sent Medina down for the count off this tricky counterpunch. When the supposedly washed Duran fought Marvin Hagler, at the height of his powers in 1983, he was able to land this same tricky punch on Hagler a couple of times.

Fig. 11

Roberto Duran fought in five different decades, and had 120 professional fights, so there is a great deal more to him than what we have examined today. Most fans and pundits know Duran more for his brilliant infighting: tearing the body up with both hands, checking his opponent’s punches by jamming his forearm into the crook of their elbow, pinching their glove in his armpit and battering them with the opposite hand. Anywhere a boxing match could possibly go, Duran had tricks from a lifetime of experience in the sweet science.

Boxing is a range game though. Any time a fighter moves up in weight he is opting into the most significant disadvantage in the sport, because he can pack on muscle but he cannot do anything to even out his reach against longer, taller opposition. Duran’s best years as an athlete were the seven years he spent as the number one lightweight in the world, but that Duran in his twenties would hardly recognize the older man who got in with middleweights like Hagler, Moore, Sims and Barkley and did some of the most beautiful boxing of his life.