UFC Paris – Namajunas vs Fiorot

The main event of UFC Paris saw Cyril Gane return to form with a Technical Knockout over Sergey Spivak. There was a tinge of sadness to this outcome because Spivak’s diligent work to improve his striking had put him on a three fight winning streak and he was beginning to look like much less of a laughably one dimensional fighter. However, Spivak’s gameplan for this fight was atrocious.

Holding a high guard, absorbing strikes and returning with his own had worked well for Spivak against Augusto Sakai, but against Gane it proved disastrous. Gane has run himself onto the fence before, but he is not the kind of man who is going to slowly amble himself towards the cage and do nothing about it. He is also a fighter who places great value on bodywork, meaning that Spivak’s high guard only handcuffed him and turned him into a heavy bag. Ultimately this was all there was to the main event.

But the real main event was always Rose Namajunas versus Manon Fiorot. Depending on who you asked before this fight Manon Fiorot was either the future of the flyweight division or just a one-two, and after the fight it seems as though she might be both. Namajunas’ smooth movement and boxing were always going to pose an interesting question for Fiorot, but Fiorot had her own riddle for Namajunas: the southpaw right hand.

We have talked before about how Namajunas is a fighter of two halves. There is the outside game, bouncing in and out and attempting to sneak in with a big punch from distance, and then there is the inside game where she makes use of her head movement and wins longer exchanges. On several occasions in this fight Namajunas attempted to pull a fast one on Fiorot with a leaping left hook or uppercut and found that Fiorot’s right hand—being much closer and faster than all of her orthodox opponents’—was already in the way.

Figure 1 shows an example of that old Namajunas trickery running up against the fast right hook. Namajunas circles to her right (b), slips back to her left (c), and enters with an upjab (d) only to get caught with the counter right hook (e).

Fig. 1

Fiorot’s right hook look fast when she held back and slapped it in as a short counter, but she was able to plant a clean one on Namajunas in the second round off a hand trap and left straight, and the right hook saw Namajunas stumble.

Fig. 2

Fiorot represents one underused facet of MMA striking in that she throws two filler strikes with the intention of only landing a third. Max Holloway, of course, could be seen doing this against The Korean Zombie last week. Namajunas, meanwhile, is one of the few in MMA who can claim to have mastered the idea of “first and third.” Throwing a strike, moving her head, and immediately throwing again in order to exploit to the opponent’s own counter. After injuring her right hand in the first round, Namajunas went southpaw for much of the bout and used either a left straight or left overhand to enter, dip and then continue the exchange.

One of the correct reads from Namajunas’ corner was that Fiorot was “pushing” her right hand. Whether it is the right hook or the power jab that she ends a 1-2-1 with, when Fiorot has thrown her right to hurt she finds herself completely bladed, shoulder’s whirled around and facing ninety degrees away from the opponent. This leaves her in a precarious position to take returning fire.

Figure 3 shows Namajunas performing a fairly conservative jab-and-dip, which sees Fiorot fling a right hook so hard that she winds up jogging off to her left.

Fig. 3

In Figure 4 you can see one of the occasions that Namajunas was able to score a decent counter. This time the southpaw Namajunas dips under the right hook and scores a left uppercut counter. Fiorot’s own refusal to use an uppercut at any point meant that Namajunas could duck under the right hook with no hesitation.

Fig. 4

In the third round, Namajunas ducked a Fiorot right near the fence and whether Namajunas’ counter punch landed or not, Fiorot threw herself onto all fours. The load up on this one evoked memories of Todd Duffee.

Fig. 5

In the Namajunas gameplan there were two major disappointments. The first was the choice of takedowns. Namajunas’ attempts were exclusively shots with trips attached which often ended up sliding down into low singles that Fiorot easily limp legged out of. They were the kind of takedown attempts where the fighter throws themselves to the ground and hopes the opponent falls with them, rather than a well timed level change and a run through the opponent.

The second major disappointment was the absence of a meaningful kicking game. There was the odd hook kick or wheel kick attempt but the very bladed stance of a fighter like Fiorot—especially as she throws her right hook—makes her vulnerable from both sides. The lead leg is vulnerable from the outside because it is often turned in. This can cause the lead leg to buckle when kicked during and exchange (Figure 6), but also means that the calf is exposed, the fighter is a bigger movement away from a check, and even weak kicks knock the fighter off balance.

Fig. 6

The bladed stance also makes a fighter vulnerable above the waist on the open side. Particularly in this open stance (southpaw vs orthodox) match up, both women should have been pounding in round kicks to the body and head with their rear leg, and yet we saw maybe two good attempts out of each fighter in the entire fifteen minutes. The bladed stance doesn’t mean that a head kick is instant death but it does mean that absorbing one and staying on balance is more difficult. A high kick against the arms followed up by punches is very effective against bladed fighters.

On the one hand, Manon Fiorot performed well against her best opponent to date. On the other hand it was the same one-size-fits-all gameplan. She will not deviate from the 1-2-1, the counter right hook, and the odd side kick (and in fact got bundled over with a counter punch off one in the first round.) She might still become a UFC champion but all her fight footage is the same and the moment a talented fighter does hit on the right ideas to punish her for her small handful of favourite techniques, she will be hard pushed to stop using them and adapt.

Elsewhere on the card, Benoit Saint-Denis proved as impressive as he is baffling. He is an overwhelming force, a talented all arounder, and yet he makes some bizarre errors. Pressing Thiago Moises to the fence repeatedly he would enter with his southpaw left hand or left body kick, and immediately eat Moises’ right hand in the aftermath. His corner were just as frustrated, he was allowing Moises to hit him for free when he had no reason to.

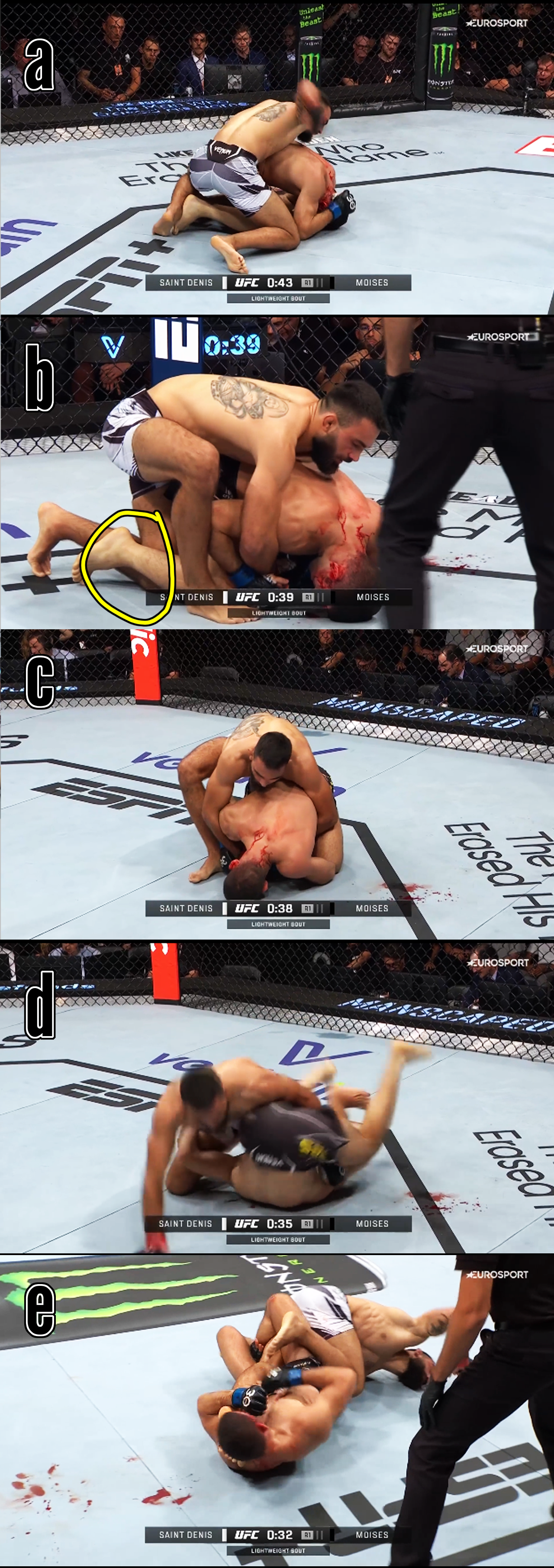

Even stranger was his work on the ground. His clinch work and mat returns were lovely, he forced Moises to turtle, and then he allowed Moises to roll on a leg. The sequence in Figure 7 played out a couple times.

In frame (a), Saint-Denis’ left foot is outside of Moises’ legs. It is a little light, most fighters would be shin stapling Moises’ achilles, but it’s safe enough. In frame (b), he chooses to place his knee on the mat, between Moises’ feet. This might be the only way to open up an offensive option for Moises from this position. This affords Saint-Denis no additional striking power or advantage in getting his hooks in, it’s just weird.

Fig. 7

In frames (d) and (e), Moises rolls onto the leg and attacks the kneebar, as he should. Moises attempted this twice in the fight and both times, Saint-Denis freed his leg in the correct way and continued working. But I cannot fathom why he would be baiting the kneebar to try and counter it, because when Moises was turtled he was already in a weak position, and attacking the kneebar didn’t seem to make him more vulnerable. Like a lot of Saint-Denis’ fighting it will remain an ugly but very entertaining puzzle.

Volkan Oezdemir got the read on Bogdan Guskov pretty quick. After eating a pair of right hand leads that bloodied his nose, Oezdemir slipped his head to the elbow side and shifted through to complete the stance switch double leg that Petr Yan loves (Figure 8).

Fig. 8

When they returned to the feet, Guskov loaded up another right hand from a day’s march and Oezdemir slipped it and came back with a left hook, before pivoting off line.

Fig. 9

Pursuing the dazed Guskov to the fence, Oezdemir switched stances and pressured Guskov from southpaw. As Guskov lashed out with one more right hand, Oezdemir slid back and to the left, throwing the open side counter across the top. The inside slip to double leg, the inside slip to left hook, and the southpaw open side counter: three perfect exploitation’s of Guskov’s tendency to lead completely honestly with a committed right hand. Someone certainly did their tape study.

Fig. 10

A completely new look came from the most unusual of places. Joselyne Edwards versus Nora Cornolle was a horrible fight full of headlock throws and accidental back takes. But in the second round, Edwards used the reverse roundhouse kick / inside crescent kick to set up a level change into an ugly but admittedly well timed takedown.

Fig. 11

What the karate folk call “gyaku” or “uchi” mawashigeri or is something that Cyril Gane will use to the head, and he and Nassourdine Imavov both throw their open stance, lead leg front kick to the body in a way that angles outwards like this kick. The kick lacks power, but it is a difficult read and unusual, so you will occasionally see it slap an opponent’s guard to set up another strike as when Anderson Silva scored a great left straight off it against Michael Bisping.

This brings us on to the other notable kick of the card. Or at least, the other notable legal kick of the card: Morgan Charriere’s feint-pause-front kick against Manolo Zecchini. Charriere—who is often the shorter, stockier man in his bouts—was able to do good work with jabs and right straights against Zecchini. A couple of good left round kicks to the body had Zecchini gasping, and as Charriere stalked for the stoppage he demonstrated a beautiful half beat fake. Squaring his hips as if to throw a right kick, Charriere took a beat, and then threw the rest of right front kick to the body. Just as with the half-jab and the half-right-straight, the pause meant that the kick could not carry as much power, but it did break Zecchini’s rhythm and the strike sunk in completely undefended.

Fig. 12

As far as bottom games go, this card’s stand out was Rhys McKee. He did some great wall walking, and when Ange Loosa tried to pin him in a half guard, McKee was able to force his way to turtle and stand, albeit taking a good amount of damage. Kleydson Rodrigues showed the classic Brazilian wunderkind problem, trying to work from his guard against a solid and disciplined top player in Farid Basharat. Figure 13 shows a sequence that played out twice and was critical to the outcome.

Basharat has landed in an almost-half-guard, with a right underhook (a). Rodrigues is fighting to keep his right knee in front of Basharat. Rodrigues’ left hand is draped across the back of Basharat’s neck and hooked in front of his left shoulder. If Rodrigues can force his right knee up to Basharat’s shoulder line he can play what is nowadays called “the clamp” and start threatening the triangle choke.

Fig. 13

If you watch any early Craig Jones matches, particularly in the gi, he had good success with this trap: jumping straight to the triangle from the bottom of half guard. It works because in half guard the top man wants an underhook, but when the bottom man frees his leg that underhook becomes a liability as it would from closed guard.

Unfortunately for Rodrigues, Basharat gets his left elbow inside of Rodrigues’ right knee (b) and he is able to force it down and step over to a flattened half guard (c). At this point Basharat’s right underhook becomes a real problem for Rodrigues and he resorts to attempting to hold Basharat in his half guard (Figure 14). Keeping the right underhook, Basharat pummels his left arm to a crossface (d). Locking his hands he pummels his left foot onto Rodrigues’ thigh and begins to pass to mount (e).

Fig. 14

Basharat was able to keep the underhook as he moved to mount and attack the arm triangle. While he failed on the first occasion, his second attempt stuck and he scored the submission. It is always fun to see someone attempting to attack from the bottom but Rodrigues might have been better served going to classical frames as soon as possible instead of holding the head, trying to be tricky, and allowing Basharat to keep the underhook.