Islam Makhachev vs Jack Della Maddalena:

Fighting in the Gaps

This is not the manner in which most expected Islam Makhachev to make his way to welterweight. When Makhachev was lining up his lightweight title shot, Kamaru Usman was the long reigning king of the welters. By the time Makhachev was champ it seemed like Leon Edwards was going to have a lengthy term of his own, and then everything began moving very quickly.

Makhachev’s friend and sometimes training partner, Belal Muhammad beat Edwards and that seemed to take the possibility of Makhachev at welterweight off the table again, and Muhammad had the unenviable task of defending his belt against the welterweight boogeyman, Shavkat Rakhmonov. That fight fell through and Jack Della Maddalena stepped in to take Rakhmonov’s spot. The young Australian, who had been on the regional scene just four years earlier, fought a blinder and took the belt. Now Makhachev’s path up to welterweight has been cleared, and the unlikely Jack Della Maddalena stands between Makhachev and what would be his greatest accomplishment: a second UFC title.

There is rather a lot to unpack in this match up, and not a great deal of time in which to do so. Today, I would like to focus on the idea of transitional offence, or “fighting in the gaps”, and some elements of each fighters game that seem destined to interact with each other.

The Double Collar Tie

The double collar tie has been an integral part of Makhachev’s game since his first fights in the UFC. He uses it to strike, to acquire stronger clinches, and to break from clinches on his own terms. As one of the closest effective striking positions, but one of the longer range clinches, the double collar tie serves as a bridge between areas of the fight. So of course a fighter like Makhachev, who has great pride in both his boxing and wrestling, can benefit enormously from frequently reaching out for his opponent’s head during a punching exchange.

As a striking position the double collar tie offers a few opportunities but the gun on the wall, that both attacker and defender are staring at throughout, is the threat of the knee strike. Jose Delgado is a hot prospect in the UFC who quickly starched Hyder Amil with a collar tie knee off a boxing combination, and almost did the same to Nathaniel Wood at several points a few weeks ago. As Amil tried to slip punches under fire, Delgado grabbed his Amil’s head and made him the meat in a sandwich on knee and hand.

Fig. 1

In this way the double collar tie either directly punishes head movement, or encourages the opponent to abandon it. In his first fight with Alexander Volkanovski, Islam Makhachev found some success with the double collar tie, so in the second fight he was utterly ruthless with it to punish Volkanovski for level changes and for simply being a short-arse at lightweight.

Fig. 2

This is where height comes in. The double collar tie is a lot easier to abuse if you have a couple of inches of height on your opponent. That is the reason that Makhachev employed it so heavily in the second Volkanovski fight, and it is the reason that gangly fighters like Jon Jones and Mansour Barnaoui find themselves drawn to it. With Islam Makhachev making the move from being a big lightweight to a not-so-big welterweight, you might rightly wonder if he can employ the double collar tie as effectively against bigger, stronger men.

But where height can be a layer of protection from the double collar tie, it does not make you invulnerable. The moment you begin moving your head, it becomes a threat again. Just look at Gabriel Bonfim, who kneed the towering Randy Brown last weekend as Brown ducked in off a punch.

The opponent’s answer to the double collar tie is always to try to maintain posture. In many instances this gives Makhachev the chance to pull them into closer, chest-to-chest tie ups, or even to level change on a shot. Here against Dustin Poirier he uses the double collar, Poirier postures and pushes towards Makhachev, and Makhachev drops down for the underhooks. Take note of the way that Makhachev uses his hands underneath Poirier’s chin, then places his head there to free his hands to grab the underhooks. It hardly needs saying but you are looking at an extremely smooth operator.

Fig. 3

Figure 4 shows a similar scenario as Islam Makhachev tears into Thiago Moises against the cage.

Fig. 4

Makhachev comes out of the handfight with a looping left (b) and a slapping right against the guard (c). He grabs a collar tie with his left and whatever he can get with his right (d), before scoring a knee to the body (e).

Fig. 5

Following the knee (a), Moises is postured upright and Makhachev changes level (b) to acquire a bodylock and push to the fence (c).

I have waxed lyrical about Makhachev’s throws with his back to the cage, and now every other fighter in MMA is starting to catch up. Something I did not notice until research for this article was how often Makhachev grabs the double collar tie with his opponent nearing the cage, and then his opponent turns Makhachev onto the fence. There the double collar tie serves as something of a wedge, preventing a takedown, but his knees are more an annoyance than the threat of a knockout. Demetrious Johnson did similar work with his double collar tie against the cage.

Figure 6 illustrates how the double collar tie allows Makhachev to improve position.

Fig. 6

Makhachev has the double collar tie and is needling Moises with decent knees, while Moises cannot attempt a takedown effectively. Moises blocks across the hips with his left hand, and swims his right arm inside (b). Swimming inside the collar tie to get your own collar tie is much more basic Muay Thai clinchwork than wrestling because it involves standing square on to the opponent, completely upright.

Makhachev pops in another knee underneath Moises’s right arm (c), and immediately drops his shoulder and pulls Moises in so that Moises’ elbow slides over the top of Makhachev’s collar (d) and Makhachev achieves the underhook (e) . From here Makhachev can turn Moises onto the fence (f) and begin applying his own wrestling.

There have also been many instances of Makhachev chaining the double collar tie and chest-to-chest clinches in reverse. Nik Lentz and Dustin Poirier dropped their hips away when Makhachev clinched them, and he let his underhook or overhook slip out to catch the collar tie as the opponent’s head came forward of their hips.

One of the weaknesses of the double collar tie in MMA is almost laughably primitive. With his back to the fence, Makhachev can land annoying knees and prevent takedown attempts, but he cannot cover his ribs. In the double collar tie the fighter’s forearms are vertical, between the two fighters’ chests, so his elbows are forward. This means that the meathead tactic of swinging hard, wide hooks into the body is actually surprisingly effective. If you revisit Nick Diaz’s old Strikeforce fights, he often encouraged the opponent to put him in the double collar tie, and pushed them to the fence in order to beat up their body.

Against Paul Daley, Diaz used his left forearm over Daley’s arms as a frame to lean his head against and protect his posture. Then he dug body shots with his free hand until he could frame out and begin firing combinations against the cage.

Fig. 7

Poirier had a number of successful escapes. He ducked out underneath, he swum in biceps ties and pushed Makhachev away, and he even held Makhachev’s triceps and lifted him to assist the duck out.

Fig. 8

But Poirier’s best answer to the double collar tie was to push to the fence and play Makhachev’s body like a Taiko drum. Makhachev circled away with the space that Poirier’s power punching provided, but Della Maddalena excels in these kind of herding along the fence situations.

The Jab and Dip

If the double collar tie is a transitional technique between striking and wrestling and vice-versa, the jab and dip is a transition between striking and defensive wrestling. Islam Makhachev’s constant hunt for head control matches up compellingly with Jack Della Maddalena’s use of jab-and-dip tactics. We discussed these at length in a recent Filthy Casual’s Guide:

Dustin Poirier performed better than anyone expected against Islam Makhachev, and a large part seemed to be that his own jab-and-dip tactics stifling Makhachev’s reactive double.

Fig. 9

Makhachev was reduced to reaching for long single legs or entering upper body clinches off the double collar tie. Poirier defended the single legs admirably until a beautiful last-minute switch up in the fifth round. It once again demonstrated that getting a step ahead on the set up changes a decent shot into an unstoppable shot. By using the jab-and-dip, Poirier constantly checked the shot and put himself in position to wrestle, even if the shot did not come.

The jab-and-dip as an answer to the wrestler is relatively new to this writer, and to MMA. We used to discuss it as a boxing tactic because it anticipates the opponent returning the instant your jab flashes in their vision, and moves you in underneath their return. It is the epitome of “first and third.” But for most of the Poirier - Makhachev fight, Makhachev was not immediately counterpunching. Instead he would give ground, and it is hard to run someone down effectively while dropping into a level change. It was also something Poirier, who loves recklessly shifting with punches as much as he loves his children, could not risk when the reactive double was always on the table.

We return to banging the old drum: ringcraft. In open space, the jab and dip protects the opponent from Makhachev timing a level change. It does nothing to prevent him retreating. As Makhachev’s back nears the fence the jab and dip forces Makhachev to either cover up, counter, or commit to an imperfect shot.

It is quite encouraging that most of Della Maddalena’s best work, and almost all of his terrific body punching, has happened when his opponent’s back is against the cage. He has done some tidy bits of ring cutting in his UFC run too, such as when he slumped Randy Brown by herding him onto a shifting right hook. Unlike an enormous number of even the world’s best fighters, Della Maddalena knows where he needs to be and can reliably put his opponent there. If he fails it is because Makhachev is a slick ring general and not because he is wandering around aimlessly at the first sign of a little lateral movement.

Constant level changes to hit the body, or simply to jab and dip, come with downsides. The double collar tie is going to be more readily available to Makhachev, even if Della Maddalena is taller than his average opponent. Furthermore, Makhachev found a couple of nice uppercuts against Poirier. In the second Volkanovski fight, where he immediately built off the successes of the first, Makhachev convinced me that he looks at tape and comes in with a good idea of what he needs to be doing for this opponent and not just what he feels like trying.

Breaking Inertia

If today’s theme is transitional work, it is worth lingering on the grappling game of Jack Della Madelena. When he first turned up on the Contender Series against Ange Loose, something about his grappling stood out. To boil it down to a word it might be called “scrambly.” Even with the knowledge that Della Maddalena only recently began working with Craig Jones, there was something Jonesian about his movement.

Perhaps it is because defensive grappling is so often marked by a cautiousness. The fear of exposing himself often leaves a fighter static on the bottom. I ranted about Dricus Du Plessis hugging Khamzat Chimaev from the bottom because that is the common knowledge: you keep your elbows in, get your frames in front of the opponent, and then begin working.

Fig. 10

But that is just the traditional outlook. If you get your frames in and keep your elbows tight, but then cannot generate movement, you are simply stuck underneath the guy just as you would be if you hugged him.

Craig Jones has some interesting ideas on being underneath traditional pins and has famously said that top side control is not nearly as useful because it is harder to hold the opponent flat. One crucial facet that Jones and Della Maddalena share—and have done since before they began working together—is an emphasis on turning to the knees and an almost refusal to re-guard.

One famous Craig Jones escape, which I do not believe has a name, is the leg pendulum he used against Meregali in the gi. Gripping inside his own hamstring across the back. When Luke Rockhold gassed out horribly underneath Paulo Costa, this grip over the back prevented Costa from advancing position or even creating space to drop short elbows.

Fig. 11

From this stalled out position, Jones can pendulum his legs to off balance the opponent. This is most often enough to get their hand and feed it to his legs, then perform a scissoring of the legs to turn their arm into a kimura-type rotation, and build up to turn them over. Against Meregali he performed the pendulum with his legs and got straight up to an elbow to throw Meregali off him.

Fig. 12

This is the balance that Jones strikes between holding (or damage limitation), and then creating movement on his own terms.

Returning to Della Maddalena, he has not used that particular escape but the way that he creates movement from the bottom is remarkable. The great old red belt, Pedro Sauer likes to say that escaping bottom pins is about “breaking the inertia.” That is to say, creating some movement and not simply trying to do the safe, well known, but ultimately ineffective escape techniques. In a sport where time on the bottom is scored just the same as if you were being punched and not punching back, breaking the inertia and making something—anything—happen is vital.

This is why you will see Della Maddalena address anything that will impede his roll to his knees. He is a diligent proponent of the “octopus guard”, even when it is not truly a guard: coming from bottom side control. This is the standard sequence that everyone is familiar with, but which still works well at the highest levels of the game.

Fig. 13

Della Maddalena gets both hands on the crossfacing arm and pushes it away (b). This frees his head and creates a space underneath Hafez’s elbow, allowing him to turn in underneath it (c). Ideally he would get his elbow high on Hafez’s back, but Hafez brings his crossface back in front of Della Maddalena (d). But he has dropped his weight back to do so and cannot prevent Della Maddalena getting up to his elbow and heisting his bottom leg out. Della Maddalena ends up in a strange all-fours position where he is still sitting on Hafez’s calf (e) but simply quad-pods up, rump first, and stands into a front headlock on the feet (f).

One rule that gets completely inverted as you transition from submission grappling to MMA is that it is better to be in a front headlock than to have guard. If submissions are all you are worried about, go to guard. If you want to get up and win fights, give them the front headlock and get your legs free to work your way up. When put down into guard against Hafez, Della Maddalena grapevined Hafez’s legs and forced him to pass to half guard in order to start scrambling, finally standing up when Hafez grabbed the front headlock.

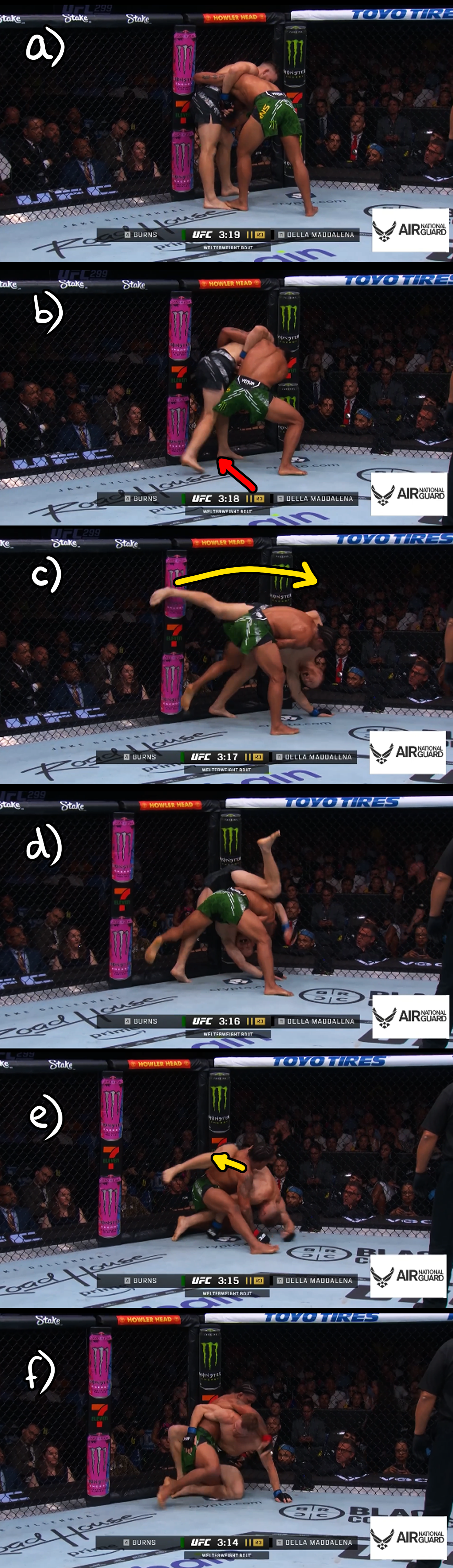

Figure 14 shows a great moment of Della Maddalena’s scrambling against Gilbert Burns.

Burns gets in on Della Maddalena’s hips (a), and cuts the corner to finish the double leg (b). As Della Maddalena is sat down he appears to grab a crotch lock: left hand between Burns’ legs, right hand over his back (c). Della Maddalena tries to roll his back to the floor, and Burns posts his right arm to prevent being rolled over the top (d).

Fig. 14

As Burns posts his arm and holds his weight back, he creates the opening underneath the elbow for Della Maddalena to scoop through with the octopus underhook (e) and, crucially, get up to his hand (f). Della Maddalena builds up to his knee and begins wrestling up (g).

The octopus position is a must-have in modern MMA. It speaks volumes that the one minute which Khabib Nurmagomedov spent on the bottom in the UFC was spent using the octopus underhook to get up. Della Maddalena’s use of the octopus position is near constant and it plays well with some of his other eccentricities.

Figure 15 shows something peculiar that Della Maddalena has done in every fight in which his opponent has tried to wrestle. If he begins losing his balance and feels as though he’s going down, Della Maddalena will throw his hips high over the opponent’s back to threaten an overhook armbar. You will recall Dustin Hazlett and Ronda Rousey scoring submissions in this way.

Gilbert Burns has the bodylock (a), and steps his left leg to the middle, rotating Della Maddalena over it (b). As Della Maddalena begins to fall, he throws his right leg and hips high over Burns’ back (c). Burns is too good to get hit with an Instagram highlight reel type of submission, and he postures up as Della Maddalena falls (e). This gives Della Maddalena space to swim through the octopus underhook and begin scrambling up again (f).

Fig. 15

Time constraints once again prevent me from a deep dive into Jack Della Maddalena’s work from standing along the fence, but in some regards he has weaponized the “standing turtle.” Della Maddalena does especially well when he can feed one hand backwards through the bodylock and either turn into the opponent or start working from an armdrag grip. His sequences of ugly harai-goshi, into switch, into turning back to the underhook are about as well as you will see someone work from a disadvantageous position.

This too illustrates an interesting reversal from straight grappling. In Jiu Jitsu, Eduardo Telles was the turtle master. But the rules of Jiu Jitsu and ADCC did not reward him if he successfully swept the opponent from the turtle because it is not considered a “guard.” There was also a limit on what he could do to an opponent who wanted to play negatively against him. What Telles didn’t have access to was the stand-up, because standing up and getting mat returned in a grappling competition would be conceding free points to the opponent.

In mixed martial arts, the stand up can break the negativity. And by leaving the mat, the turtle fighter gains access to some interesting throws. Jack Della Maddalena’s throws are not pretty, but they make the opponent choose between letting go, or falling onto the bottom and possibly getting stuck there.

Della Maddalena throwing his hips high over the opponent’s back links with the idea of inverting. This is seen as a noodly guard player skill, but Della Maddalena showed another side of it against Belal Muhammad. Figure 16 shows the action.

Belal Muhammad has ripped out of a kimura attempt and Della Maddalena has begun rolling under to enter a leg entanglement (a). Della Maddalena fully inverts by rolling his head in underneath him (b). Muhammad sits back (c) to prevent Della Maddalena rolling him forward and exposing the leg. As Muhammad sits back, Della Maddalena pushes his hips back and pops his head out as if performing a backwards roll. Having back rolled into turtle, with none of Muhammad’s weight on him, he runs up to the feet (d).

Fig. 16

Della Maddalena even threatened a buggy choke against Hafez, something his stocky build makes it hard to finish. But it had the effect of making Hafez lift his head and break the pressure of the pin, allowing Della Maddalena to get to work with something else. As weird as it often looks, Della Maddalena embodies the principles of “push, pull” and “kuzushi” in mixed martial arts.

Other Disorganized Thoughts

The roundedness of Islam Makhachev’s offence is what cuts most of his opponents off at the knees. That effect is magnified by the sheer number of links he has between the striking and wrestling parts of his game. His truly multifaceted skill set also means that Makhachev can fully press advantages others do not.

A glaring example would be that as the stronger wrestler in most match ups, Makhachev gets the advantage that his opponent is reluctant to kick. For most wrestlers this is enough, but Makhachev actually pushes this advantage by using his own decently effective kicking game. If you are fighting a striker and he cannot operate beyond boxing range, you might be able to beat him with meat-and-potatoes kickboxing. In fact, Makhachev has often done that. And as Dan Hooker and Drew Dober found out, the moment you kick back Makhachev is excited to step in and bundle you over with half the effort of a more proactive takedown attempt.

But one of the reasons that Della Maddalena always stood out was that he does lots of things other fighters cannot or will not. The switch hitting and consistent body work, the ring craft, the head movement: these all barely exist at the highest levels of this sport. The head movement is particularly interesting because Della Maddalena is not the most elusive fighter on earth: he moves his head to create more openings to hit his opponent. As a test for Islam Makhachev it is not simply that Della Maddalena is bigger, it is that he might be the first fighter to even question Makhachev with a lot of the striking game that just does not get showcased in MMA.

Sometimes I can write an article about the interesting ways in which two fighters games match up, and then the fight plays out in a completely different area. But with Makhachev and Della Maddalena it is just so difficult to imagine these tendencies not smashing straight into each other.

A huge part of Makhachev’s philosophy is getting behind the opponent and staying behind them, and a huge part of Della Maddalena’s work getting up is to put the opponent behind him and threaten with throws and switches until he can turn back into them. Della Maddalena’s ground game is built around wrestling into the opponent and making them take the front headlock instead of pinning him flat. Meanwhile Makhachev has mastered a short-arm D’arce choke that has had his last two opponents tapping out as if their necks were about to break. Makhachev grabs the double collar tie in nearly every fight, and Jack Della Maddalena is the only good body puncher he has ever met. Makhachev excels at controlling the pace and hiding behind his long southpaw kicking game, yet Della Maddalena is a phenomenal pressure fighter and—as Gilbert Burns can attest—counters well off parried kicks.

There is no flaky chin. There is no suspect gas tank. If there is a catastrophic undiscovered weakness in either man, it has been hidden deep beneath their many other skills and virtues. On the surface level, both men are a hard ask for anyone in the world. And that is all I ever want: to see two truly great fighters crash into each other until one can finally find a crack in the armour.