Despite Alexandre Pantoja and Brandon Moreno having a Fight of the Year worthy scrap and Alexander Volkanovski flawlessly dispatching yet another top contender, it was Dricus du Plessis who stole the show at UFC 290. That was not because he surprised everyone out of nowhere—the basically unknown Alexandre Pantoja did that in the co-main event. It was because fans already knew him and had witnessed him in sloppy brawls on UFC main cards that they were adamant he had nothing for the smooth technician, Robert Whittaker.

This writer’s takeaway from the fight was that it came down to mechanics versus tactics. Mechanics are the elements that a fighter brings into every fight. They are the movements trained into habits that only break down when a fighter is exhausted, hurt, or emotional. Tactics are choices made specifically within the context of a match up. Robert Whittaker’s jab, one-two, and high kick are all slick and play off each other, but they are the weapons that he takes into every bout. His mechanics and brilliant control of distance ask a lot of tough questions of his opponents, but those questions remain fundamentally the same. Dricus du Plessis does not typically fight southpaw for much of the fight, doing so was a tactical choice he made solely for Robert Whittaker.

Function Over Form

To begin with, it looked as though Whittaker was going to get in his groove and cruise to another unanimous decision. His distancing was perfect, and he set himself up just beyond the range at which his opponent could comfortably kick. This is an idea that we have called The Distance Trap: using a frustrating control of range to convince the opponent to overcommit while staying relatively safe from harm yourself.

The first round was full of Du Plessis trying to wade forwards and Whittaker making short bounces of both feet to correct the range. This is the trick of point fighting that we have covered a hundred times before: get the opponent stepping forward without thinking, or stepping too deep because they anticipate your retreat, and you can intercept them at what seems like double speed and with double the impact.

Figure 1 shows an example of Du Plessis taking what we call an “extra step.” He wants to kick Whittaker with his left leg, but he is too far out and has to take a small step with his lead foot first (b). The lead foot is the telegraph that informs Whittaker it is time to strike and he immediately shoots a jab up the centre (c), knocking Du Plessis off balance.

Fig. 1

From Kyoji Horiguchi back to Lyoto Machida, this stepping up the inside of a kick is a staple intercepting counter of the “karate-boxer.” It always starts from exaggerating the distance and drawing a dumb, “throw and hope” kick instead of from trying to crowd the kicker. Part of the trick is in striking down the centreline, but drifting off to the opposite side from the kick, in order to take some of the pop off it should it still connect.

Another common response to the karate-boxer’s exaggerated distance is to try a step up kick off the lead leg. These are even more obvious and lead to some spectacular counters, such as Kyoji Horiguchi sending Manel Kape flying through the air. Figure 2 shows Whittaker intercepting Du Plessis as he tries a step up kick.

Fig. 2

This brings us to our first example of Du Plessis executing an intelligent tactic, but perhaps not in the slickest way. Studying this fight again, it is clear that Dricus du Plessis came in with the intention of using feints to dull Whittaker’s senses and slow down his rate of work. Where a more conventional, polished striker might feint and drift back only a little to stay in position to strike, this fight saw Du Plessis move forward, and then try to cover up and rapidly retreat off every time Whittaker launched himself forwards. Visually it was very strange, but the effect was the same: Whittaker became less confident in anticipating Du Plessis and Du Plessis was able to get closer to Whittaker as the fight progressed.

Du Plessis also made use of a rather ugly jab-and-dip to try and advance through Whittaker’s counters and to “counter-the-counter”.

Dricus Du Plessis seemed keenly aware of Whittaker’s tendency to duck into his opponent’s chest after a bursting entry, and also to lower his head on the dipping jab. Even when Whittaker scored with his hands, Du Plessis would try to punish him for dipping with the uppercut or the double collar tie and knees. Figure 3 gives a clear example.

Fig. 3

As Du Plessis awkardly threatens to step in, Whittaker throws a front kick to the body which Du Plessis pulls away from (b). Whittaker pulls his foot back and places it down underneath his hips and closer to Du Plessis, enabling him to leap in as he did in his famous knockout of Brad Tavares (c). In this instance Whittaker leaps into a dipping jab (d) which hits Du Plessis. But Du Plessis loads up on a counter uppercut (e) which just grazes as Whittaker pulls his head back to upright (f).

Figure 4 shows a similar idea as Du Plessis leads with a right straight, Whittaker ducks it, and Du Plessis grabs Whittaker in his stooped over position and lands a knee.

Fig. 4

The hole that Du Plessis claimed to have spotted in Whittaker was a difficulty with the southpaw jab. This is intriguing because in Whittaker’s last few performances against southpaws—Gastelum, Vettori, Till—Whittaker has looked at the height of his powers. But then, as has always been the theme in the Killing the King articles, you can still learn about a fighter’s habits even when they’re looking great. Also with five fights against switch hitters in Adesanya, Cannonier and Romero there are a couple more hours of tape of Robert Whittaker fighting southpaws who aren’t even considered southpaws. Personally, I hadn’t clocked this difficulty with the southpaw jab, but Du Plessis scored the same stiff southpaw jab three times in the course of this fight, en route to a knockout.

Looking at the footage of these connections—one of which can be seen in Figure 5—it seems that because Whittaker’s long distance jab comes off his thigh, and Du Plessis’ comes straight from the line of his shoulder, Du Plessis can shoot over the top of Whittaker’s punching path while Whittaker’s left side is exposed. It is worth noting that Whittaker’s tendency to dip to his right as he jabs meant that Du Plessis was able to land on his temple and jawline with these shots. The final right jab that began the technical knockout intercepted Whittaker as he lunged into a right straight, thrown off his chest with his left hand still low.

Fig. 5

Rough and Tumble

Though fans derided it, Du Plessis had already demonstrated some craftiness on the mat. His fight with Brunson was seen as a sloppy scramble fest but there was more to it than that. Here is an example that impressed me at the time:

I have waxed lyrical about the empty half guard before when Rani Yahya’s old man jiu jitsu saved him from a beating after he gassed out hard against Enrique Barzola. But Yahya uses the empty half to bait the opponent to knee slide their leg free and then turns to his turtle. Du Plessis’ use of his legs to pendulum himself towards a seated position and recover half guard is something I hadn’t seen in MMA. Using the legs to pendulum and create space from the bottom of side control—rather than simply trying to bridge and shrimp on repeat—was something that Ryan Hall was preaching about over a decade ago on his original set of DVDs. It returns to our constant theme that in MMA, with limited time to work and strikes as a constant danger, creating movement from the bottom is far more important than slow, incremental improvements of position.

For the most part this fight demonstrated Du Plessis’ top game which looks like it is no fun at all to experience. It started goofily enough, with a successful head and arm throw in men’s MMA. As much as osotogari as it was a headlock, the important point was Du Plessis’ follow up on hitting the mat. The scourge of women’s MMA is fighters hitting the head and arm throw, winding up in a bad scarf hold, and losing control as the opponent turns to their belly and comes up behind.

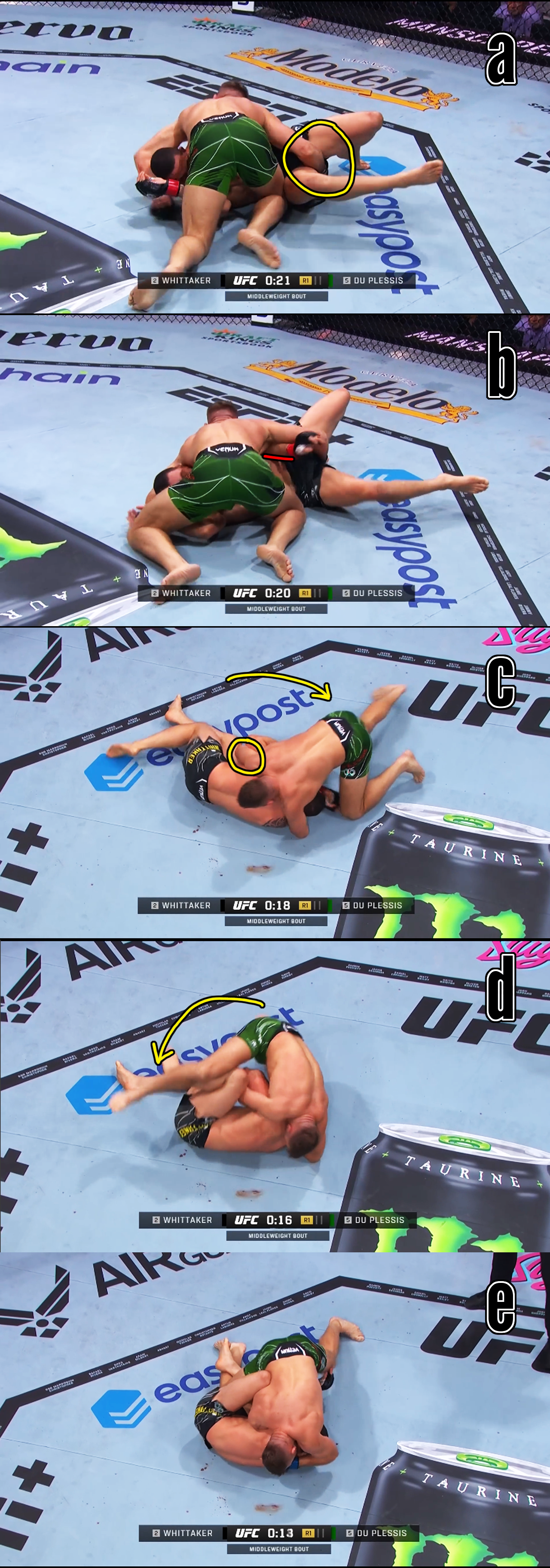

Figure 6 shows how Du Plessis slowed the scramble down. After landing with the headlock, Du Plessis high steps over Whittaker’s legs (a), (b). Whittaker gladly accepts the half guard, which combined with the underhook puts him in a great sweeping position (c). But as Whittaker begins switching his legs to come up to the dogfight, Du Plessis has time to turn to throw in the whizzer (d) and keep Whittaker in front of him (e). The embarrassing post-throw back take is off the table now at least.

Fig. 6

In Figure 7 you can see how Du Plessis consolidates top position and halts Whittaker’s progress towards a sweep. Whittaker’s hands are still locked around Du Plessis as they were when the two men landed from the throw (a). This means that when Du Plessis punches his whizzer through to the top of Whittaker’s thigh (b) and cups Whittaker’s left triceps, he can easily force Whittaker down onto his shoulder and kill any get ups (c).

Fig. 7

With Whittaker flat on the mat, Du Plessis can free his right hand to land one elbow at a time (d). Whittaker unlocks his hands and gets up to his elbow (e). This is necessary to begin a good get up.

Figure 8 shows how Du Plessis shot his left hand deep from armpit to neck (b), dived over Whittaker’s head and flattened him back down to the low shoulder once again (d). If Du Plessis can lock his choking hand inside of his biceps he can d’arce choke Whittaker and secure the finish.

Fig. 8

The beauty of the d’arce is that it severely limits the bottom man’s options. He isn’t getting up and he’s very unlikely to sweep if you’re doing your job right on top. Most of his effort is devoted to keeping his back from being crumpled in and on trying to keep the top man from getting a hand to biceps connection. This means that the top man can posture up momentarily and land an elbow with almost a guarantee that the bottom man will not be in position to defend himself. If the bottom man brings his head close to avoid the elbow, he may have just put himself closer to being d’arced as the top man drops back down.

Fig. 9

When Whittaker recovered his guard and tried to lock Du Plessis down in a closed guard, Du Plessis demonstrated the seldom seen Tozi pass. The Tozi pass—like any good grappling technique—has a whole bunch of different names. It is sometimes called the Sao Paulo pass, the Roger Gracie pass, the Wilson Reis pass. Roberto Tozi was the first guy famous for doing it so let’s go with that.

The unique selling point of the Tozi pass is that you can break open an opponent’s closed guard and begin passing, without standing to do so. It is what every old, overweight white belt wants most, but the fact that you seldom see it should tell you that it’s tricky. In fact, Roger Gracie is famous for both using this pass and having an unpassable closed guard, and advises that you should always stand to open the guard.

Most Tozi passing begins with an underhook (though Wilson Reis often just used a biceps tie). Half the difficulty is in making sure the position is about the top player’s underhook and not the bottom player’s overhook. Many closed guard attacks like the triangle and omoplata begin from the bottom man having the overhook. But the top man’s underhook is critical in Tozi passing because it stops the bottom man from popping up on the top man’s back.

One form of Tozi pass is the one Wilson Reis begins against Ryan Hall here. Reis switches his hips and uses his thigh to unbuckle Hall’s ankles, before stepping over the bottom leg. Reis also used this in Bellator against Shad Lierley and it was easily the coolest thing he did in his MMA career.

The Tozi stack is a very nasty variation of the Tozi pass where the top player gets up on his toes, walks himself around the opponent and uses his free arm to pull the opponent’s head in at the same time. The effect is to fold the bottom man in half and make it almost impossible to keep his ankles crossed.

When the bottom man opens his legs he is already in a compromised position and the bottom leg can be stepped over or underpassed. Du Plessis opted for the underpass.

Du Plessis consolidated position with what we have been calling “catch wrestling side control” for want of a better name. Figure 10 shows it: it' is the one you see in old books and it resembles the pro wrestling “hook the leg” cover. You don’t see it much in grappling because bottom players like to try to push the top man’s head between their legs and throw up reverse triangles. But the benefit of the position for MMA is that with the arm between the opponent’s legs (a), the top player can block or at least significantly slow a roll in either direction. Glover Teixeira used it frequently against Jiri Prochazka.

Whittaker dug an underhook (b) in order to begin slowly walking his hips out and trying to turn to his knees. When the underhook came in, Du Plessis removed his right arm from Whittaker’s crotch, circled towards Whittaker’s head and locked his hands in a front headlock (c). Now that he had Whittaker’s head and arm, he circled back towards Whittaker’s legs, stepped over them and got back to half guard, starting the sequence of d’arce choke hunting and elbows over again.

It has taken him finishing one of the pound-for-pound most skilled competitors in the sport, but people are at last showing Dricus du Plessis respect for more than a goofy puncher’s chance. But even in this career best performance there was plenty of food for the doubters. Du Plessis’ chin is up like Derek Brunson’s on every attack, he closes his eyes when he gets into exchanges, and to achieve the finish he simply sprinted after a staggered Whittaker, flailing wildly. Yet Whittaker himself is known for his clinical precision seventy percent of the time and swinging like a wild man the other twenty five. The question is if Du Plessis could magically remove all those obvious bad habits overnight, would he actually perform much better than he is currently? Or is that sloppiness part of his strength?

——————————————————————————————————————

If you are still in the mood for UFC 290 hype, consider reading my study on the enormously talented but infuriatingly wild Alexandre Pantoja, or Advanced Striking 2.0 - Alexander Volkanovski.