Alex Pereira's Path to Redemption against Magomed Ankalaev

Magomed Ankalaev snuck up on the light heavyweight title at a glacial pace. He suffered a comical last second submission loss to Paul Craig. He wasted more than a year in do-overs against Ion Cutelaba and Johnny Walker. A draw in his first title fight annoyed the UFC brass so much that both participants were left in the rear view mirror and the belt was slapped on a completely different fight. When he finally arrived for his second shot, against the UFC’s last living star, Alex Pereira, Ankalaev made good and won the fight on all the scorecards.

That fight had the curse of being a close, largely uneventful bout between two fighters with obnoxious fanbases, so it has been re-examined a hundred times in the six months since then. Now on the cusp of the rematch, it is time to add one more voice to the annoying chorus as we ask what Pereira can do to reclaim the crown and how Ankalaev can build off his successes to keep it.

The vast majority of fans and pundits scored the first fight three rounds to two, for either fighter which hardly reads as a dominant performance that Pereira cannot come back from. Yet even Pereira’s biggest supporters recognized the key issue of the fight: Pereira did not—or could not—throw confidently. There were likely a number of reasons for this, the chief suspects being Ankalaev’s effective pressure, the handfight, and the threat of the takedown.

Effective Pressure

The threat of Alex Pereira can be divided into two parts. At close range there is the ludicrous left hook that can put top light heavyweights to sleep instantly. At long range there are the no-tell low kicks that quickly have the opponent hobbling. In order to get close enough to apply pressure, Ankalaev had to get through kicking range and he did that admirably.

As we discussed on a Filthy Casual’s Guide some time back, Alex Pereira has worked diligently to shave all the tell off his low kicks, but that does not mean they are non-committal. During a kick the work of the upper body is mostly to counterbalance. With no upper body involvement, Pereira misses a kick and looks as though he has just stepped on a skateboard by accident. His kick carries him out of position and he cannot effectively follow up.

This is a stark contrast to the work he did with traditional low kicks to the thigh in kickboxing, where the whole point of the low kick was that he could counter the opponent with the left hook when they tried to step in off it.

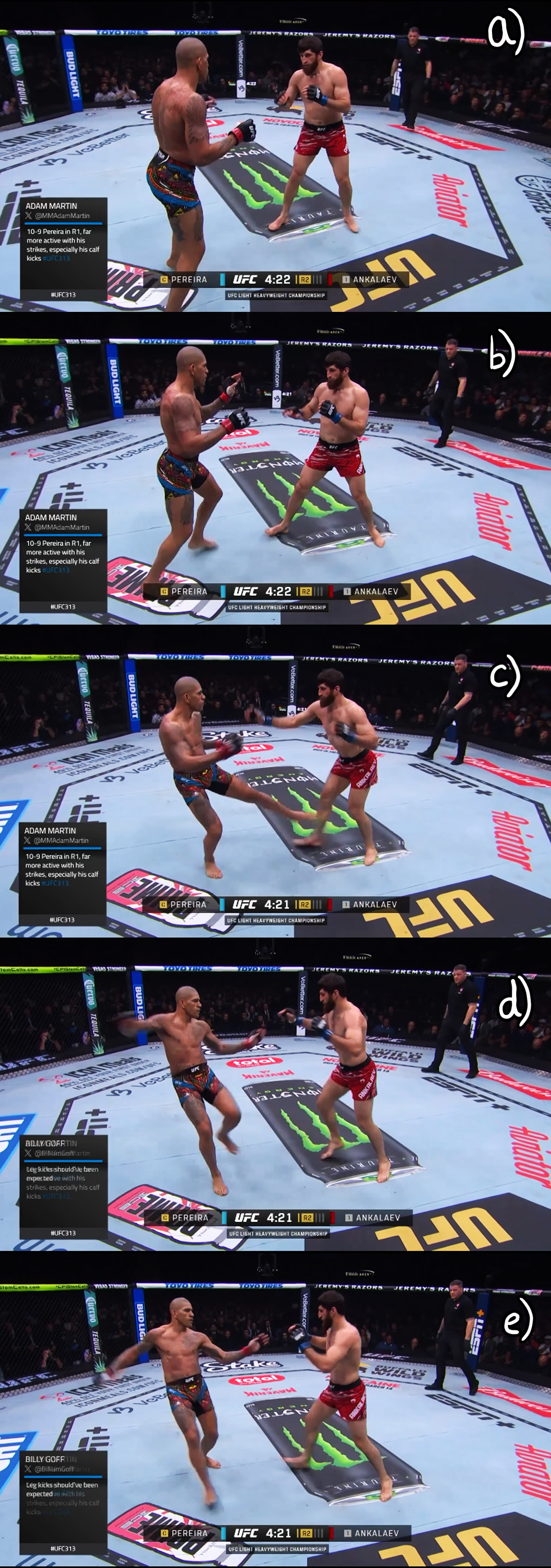

In the early going of the first round, Pereira was able to skip around, get outside Ankalaev’s lead foot, and step up into his lead leg calf kick.

Ankalaev soon began withdrawing from the kick and letting Pereira throw himself off balance, then trying to push him back as he recovered.

The low kicks were far less of a problem for Ankalaev once he was standing close enough to pressure Pereira. When Ankalaev was on top of Pereira, Pereira could not find the space to step around the lead leg to get the angle, nor could he risk the step up. I have heaped praise on Pereira for making his step-up calf kick as comfortable and effective as his regular calf kick, removing the issue of his opponent switching stances, but there is still a preliminary motion in the step-up. It will always be slightly slower, more telegraphed and cover a different distance. With Ankalaev up in his grill, Pereira was much less inclined to throw the calf kick for fear of being force fed the left straight.

Pereira fans were also astonished by the lack of effectiveness he showed with his left hand. Usually the death touch, he barely got it off against Ankalaev. This was partly because of the handfight, an idea we mused on in the Filthy Casual’s Guide ahead of the fight, but not entirely.

Pereira’s left hook is a murderous counter punch. Palm in, elbow low. It is tailor made to flank in for a t-bone collision as the opponent is punching straight at him. Sometimes he will swing it wide by opening up at the elbow. Even against the southpaw Jamahal Hill, Pereira’s left elbow stayed low and his punch came up on an angle across his body. This stands in stark contrast to Magomedov Ankalaev’s southpaw right hook, which is built for open stance exchanges. Ankalaev’s right hook is thrown wide, often leaning back, with the elbow high, arcing over the opponent’s lead shoulder and arm.

The handfight clearly played into it, as Ankalaev stuffed the lead hand to kill time, to break offline, or to throw the left front kick. In the more recent Filthy Casual’s Guide we discussed how Pereira tried to break his lead hand free against Adesanya by dropping it below the handfight, while remaining in range. This is dangerous for the most obvious reason in the world: your hands are doing a job when they are in your guard. But dropping the hand below the handfight is still a legitimate way to free it, and Ankalaev routinely did it not by letting his hand fall to his thigh, but by level changing to provide the threat of the takedown as he windmilled his hand up on the outside of Pereira’s.

Most of Pereira’s left hooking woes seemed to come from discomfort pulling the trigger against a competent southpaw who was moving his head, and throwing back after everything Pereira threw. That and the fact that any time Ankalaev entered, it could be to change levels onto Pereira’s hips.

Ankalaev’s pressure was only possible because of his comfort, or even fearlessness, under fire from Pereira. His simple but smooth boxing was more than enough to keep him relatively safe and Pereira in danger when they came together to trade. However it would obviously be absurd to ignore the threat of the takedown. The threat of the takedown is all it was because in twelve attempts Ankalaev never got Pereira off his feet. Through Ankalaev establishing the threat in round one, and committing to minutes at a time of grinding along the cage in round four, Ankalaev’s wrestling changed the fight.

Hypothetical Gameplans

It is curious to see Pereira in a match up where his opponent’s aggression is not playing into his strengths. Usually the threat of Pereira’s Dim Mak left hook in a firefight keeps his opponents out of range—where he picks at them with low kicks and where they have to telegraph their charges and takedown attempts. To break the pressure it would usually be smart to look for intercepting weapons such as elbows and knees. These are difficult or risky to attempt out in the open but with an aggressive opponent the chances are provided more readily. The damage from an intercepting elbow or knee can be fight ending, or more likely can force the opponent to lay off the pressure for a while.

The problem is that we are not talking about Song Yadong versus Cody Sandhagen, in-your-face recklessness, we’re talking about a measured, creeping pressure. Ankalaev kept himself just close enough to make Pereira uncomfortable but he was never just plodding forward in a way that Pereira could easily put a lead on him and intercept with certainty. He was forever ready to lean back, slap over the right hook and return with the left straight. In fact, Pereira attempted a couple of intercepting knees on Ankalaev in the first fight and it was changing his mind halfway through one of these that got him visibly rattled with punches in round two.

This writer’s main lesson from the first fight was that Alex Pereira does not care for throwaway punches. His combinations are almost exclusively working-the-heavybag type flurries on a stationary, covering opponent. It would be natural to learn this from kickboxing, where putting on the earmuffs is the main defensive strategy. But against an opponent who can slip punches decently, a degree of “bullshit volume” is necessary to land effectively. Here is a great example of Pereira lunging deep to sell out on a right hand to the body and getting easily countered with the right hook, then struggling to get back to position.

One of the great principles of martial arts and combat sports is that if the opponent’s defence involves them moving, something has changed and they are now open in a different way. Ankalaev dropped away and extended his stance to set the right hook when Pereira started throwing and that can be exploited. That is the time to low kick. Not as Ankalaev is pressing forward, waiting to jam the left straight up the middle. It would be terrific to see Pereira pump two or three straight punches—focusing on staying long and safe, not landing—and follow with hard low kicks as Ankalaev spreads his feet to start swinging. You can see Ankalaev suffer the effects of being low kicked while his feet are spread in both his match with Jan Blachowicz and his first fight with Johnny Walker. He is not immune to low kicks: he addresses low kicks, and then tries to use the part of his game that makes him vulnerable to them.

It would also be good to see Pereira adopt the straight spamming tactic that works well against tricky southpaws. This is simply to put the focus on 1-2-1 and 2-1-2. Throw the jab and the right straight at the same length, occasionally substitute the jab for a slap down of the lead hand. Move the feet with the punches, and only really care about landing the second or third, never both or all. The whole point is to have volume out there, making him move his head and hopefully catching him as he leans. It is helped by pulling up short from time to time and letting him whiff his counters. A perfect example of this kind of unattractive piston-pumping against a smooth, elusive striker was when Trevin Giles got the better of Carlos Prates for much of their fight.

Regarding the wrestling, the first fight demonstrated the cheat code of MMA that most viewers hate. Once a fighter has a clinch along the fence, all of his opponent’s action is defensive and he, even by simply keeping the clinch, is considered the offensive fighter.

Ankalaev accomplished nothing in the clinch except keeping the clinch, while Pereira exhausted himself trying to break it. And finally Pereira saw enough space to get away, but the time was gone.

This is the fundamental issue at the centre of MMA right now. Time spent with your back to the cage is a portion of the round lost, even if the attacking fighter fails in every attempt at a takedown. It seems as though the only way to counter this—if you cannot break quickly and strike on that break—is to threaten a takedown of your own. The example we always use is the overhook throw. Whether it is harai-goshi, stepping all the way across the opponent, or uchi-mata, mule kicking the inner thigh—the overhook throw is one of the few takedown options the fighter has from the upright clinch with his back to the fence. Islam Makhachev is the master of this. He will attempt to circle out with the single or double collar tie, or the underhook, but he wastes no time before trying for a throw of his own. Often he will use short, well aimed knees strikes to get the right grips first.

Makhachev is obviously an extreme example because he most often wants to force the grappling. A better example would be Jack Della Madelena. The offensive portion of his game is as striking focused as Pereira’s, but when the opponent pushes him to the fence, he threatens to put them on their back. Even the best grapplers in MMA do not want to be thrown into bad position because it takes so much time to get back up and reversals of position against good opponents are hard to achieve. Against Belal Muhammad and Gilbert Burns, Della Madelena bladed his body when they pushed to the fence and started to fight two-on-one against one hand. From here he was able to step through into an extremely ugly throw attempt that immediately made the opponent give up position and created space to escape.

Similarly he was able to apply the switch when Muhammad came in low, and threaten Muhammad with bottom position. Even when he turned off the cage with the underhook, JDM would come back in on a single leg to make it clear to Muhammad that he would push the issue in the grappling if Muhammad wanted to wrestle.

It is obviously a long shot to hope that Pereira has put time into attacking with his back to the fence, but this seems to be where the next evolution in the long battle between wrestlers and anti-wrestlers is happening.

For Magomed Ankalaev, it feels as though the first fight was more decisive than it appeared. He won three rounds to two on most scorecards, with plenty of reasonable pundits even giving the fight to Pereira, but the inescapable fact is that he made Pereira look ineffective. There was a moment just after the Jamahal Hill fight where it seemed as though all Pereira had to do was touch his opponent with the left hook and all their work would be undone. Ankalaev’s wrestling was no doubt a factor in the way the striking unfolded, but his handfighting, his comfort under fire, and his ability to absorb a decent punch and immediately throw back all had Pereira looking increasingly uncomfortable. I have no doubt that Jiri Prochazka, Jamahal Hill and Khalil Rountree wanted to get in Pereira’s face and make him respect their power, but Ankalaev is the only one who actually did it. And it didn’t seem to be his power that was scaring Pereira so much as the fact that he always returned on Pereira’s shots, even if Pereira landed.

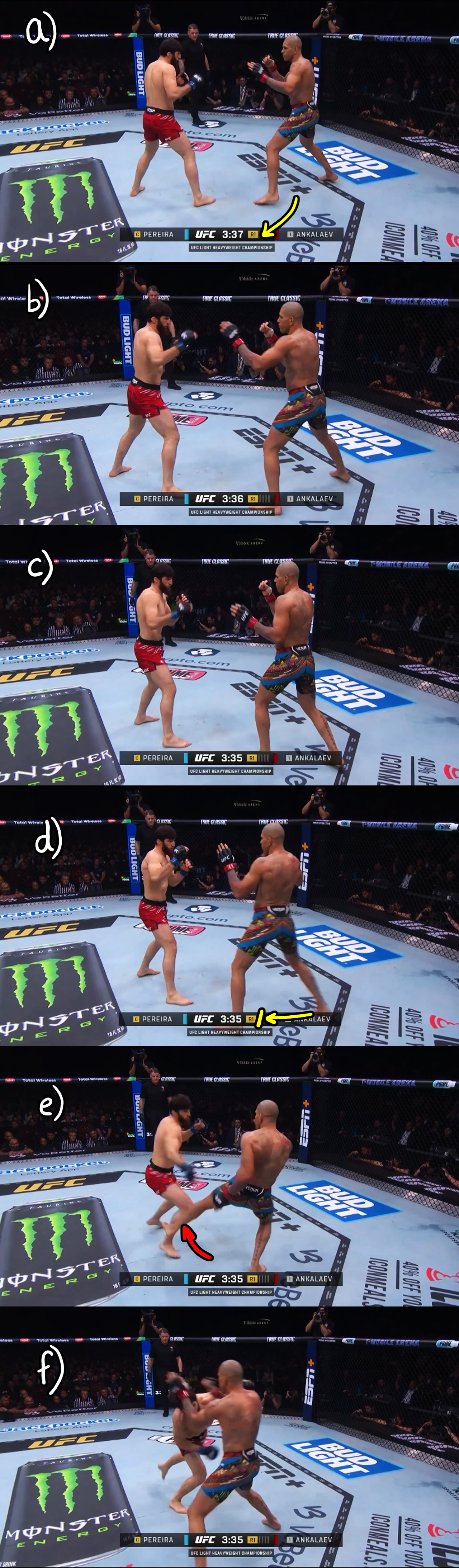

Two understated successes that Ankalaev had in the first fight that I would like to see applied even more generously were his kicking game and his work from orthodox stance. The left front kick to the body out of the handfight was a great point scorer and physically pushed Pereira back towards the fence. But Ankalaev also had success with his own low kicks to the thighs after checking or evading Pereira’s calf kicks. And the switch hitting was a real surprise because it seemed as though Ankalalev’s southpaw stance would be the main thing giving Pereira issues. When Pereira began reaching with his lead hand, Ankalaev would step through to orthodox, use his left hand to hit the inside hand trap, and wallop Pereira with a right hand in the exact same way Adesanya had repeatedly done.

It is always tempting to say that Ankalaev should have got on the wrestling earlier, but in this rematch that could be a misstep. Pereira will have spent months cage wrestling and an immediate success against a first round shot to the fence will only give him confidence. So much of Ankalaev’s success in the first fight seemed tied to Pereira feeling uncertain and tentative. It might be worth coming out for the first round, touching Pereira’s legs with a level change and a knee slap, and immediately swinging on him. Jiri Prochazka even had a little success with this when he had not established a takedown threat at all. Landing a few good blows in this way would serve to shake up Pereira’s confidence from the get go, and also to steal the first round. Ankalaev looked fine in the first round of the first fight but all three judges and most pundits gave it to Pereira.

The UFC have to be hoping that Pereira can pull this off, because he is the last thing the company has that even resembles a star. But the move up to light heavyweight was always going to be accompanied by the possibility of a light heavyweight who can wrestle a bit. The fact that the one light heavyweight using his wrestling also has some of the nicest boxing in the division is not something Pereira could have bargained for.