Advanced Striking 2.0 –

Israel Adesanya

Winning a UFC title and defending it multiple times as a kickboxer is an impressive feat, but the other side of the coin is perhaps even more impressive. Israel Adesanya was able to excel to the highest levels of kickboxing while focusing primarily on becoming a great MMA fighter. Adesanya is not an athlete who fought a whole combat sports career and then had to adapt his skills to the cage, but instead pursued MMA and kickboxing simultaneously for a significant time.

While no one could fight the exact same way in a kickboxing bout as they do in an MMA one, the cross compatibility of Adesanya’s striking style is astonishing, and this is because it is founded in timeless principles and not sport specific techniques.

Fig. 1

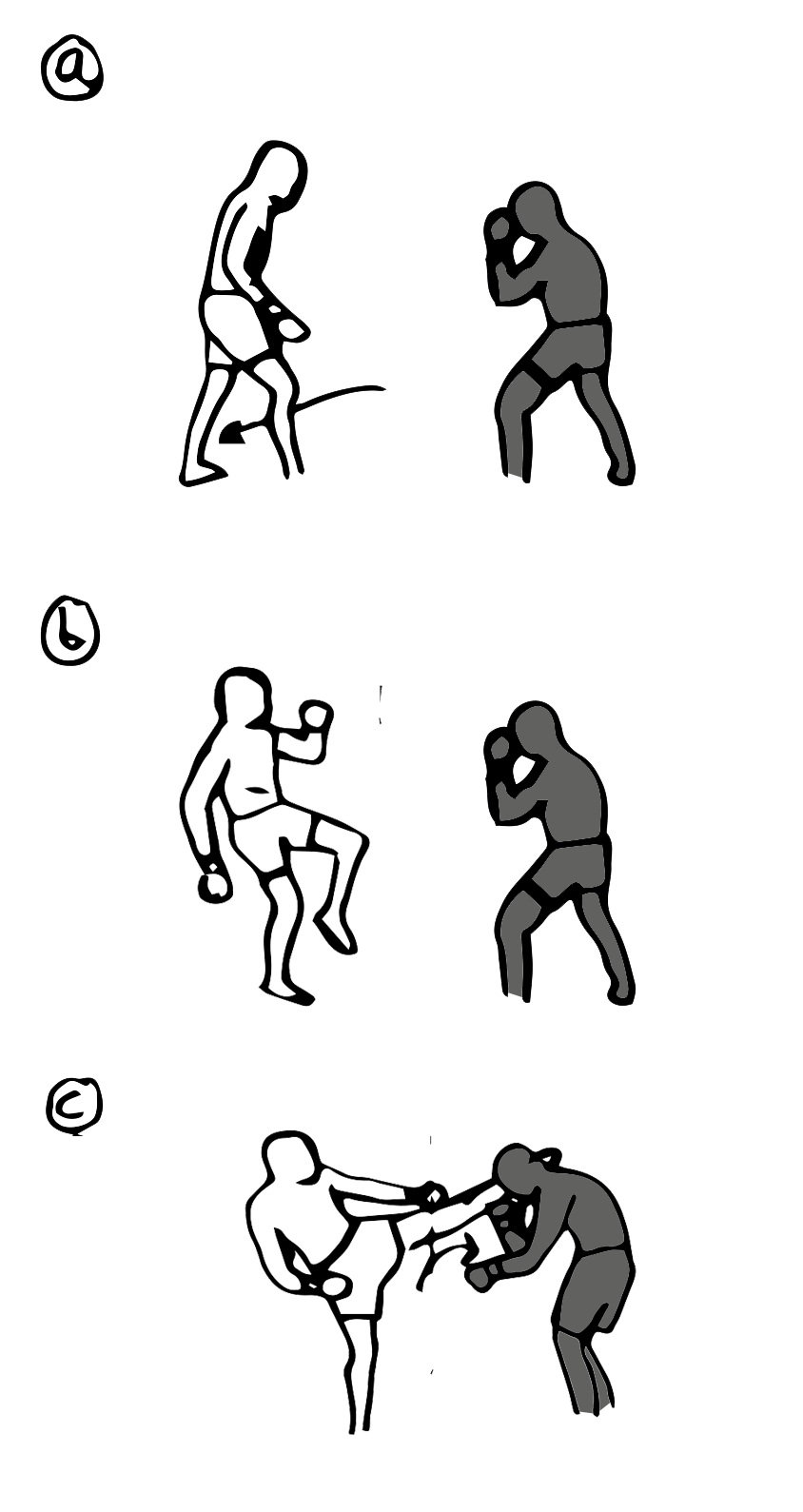

Sequencing off the Step-Up Kick

Alexander Volkanovski has been making a strong case for the step-up inside low kick in mixed martial arts. He hammers it in as a powerful lead, and after establishing it as a threat he can use the telegraph of the step-up to force reactions and set traps. Volkanovski trains mainly in New South Wales but travels to Auckland to train with the City Kickboxing team and understandably there has been some cross-pollination of styles. Adesanya is a second UFC champion making use of the step-up kick, but often in a different context.

For Adesanya the step-up kick is transitionary technique. He uses it to switch from an orthodox stance to a southpaw one and place himself in position to capitalize with a secondary attack. This is akin to the way that Zhang Weili uses her inside low kick to move from a square stance to a bladed one from which she can side kick.

Figure 2 shows Adesanya initiating with a step-up left kick to the inside of his orthodox opponent’s lead leg (b, c). He retracts the kicking leg and places it behind him (d), putting him into a southpaw stance and changing the stance dynamic of the fight from closed stance to open stance. As the opponent pressures in on him, Adesanya takes his head offline to the right and shoots a left straight to begin a punching combination (e).

Fig. 2

You can watch a kickboxing match between two mechanically solid kickboxers that never becomes anything more than a turn-based exchange of combinations. Adesanya’s inside low kick to stance switch can be seen as the start of a longer combination with a break in it, or a reconnaissance technique to try and draw a reaction from the opponent and capitalize on it. If the opponent has worked himself into that all too familiar “your turn, my turn” rhythm, Adesanya’s inside low kick—followed by a conspicuous retreat—essentially invites the opponent to take his turn. Just as the opponent thinks he is claiming the initiative, Adesanya threads an easy counter straight down the centre and snatches the initiative back for himself.

In Adesanya’s first match with Alex Pereira, Pereira had struggled to come to terms with the fact that while Adesanya was mainly presenting an orthodox stance, all his best hitting was happening as a southpaw. This was because Pereira tried to crowd him off his annoying kicks. Adesanya might also meet aggression off his set up inside low kick by leaning back into a counter right hook or intercepting with a left knee to the abdomen.

When Adesanya throws his step up kick and retreats to southpaw the other option that his opponent is presented with is to practice some self restraint and hold off on pursuing Adesanya. Figure 3 shows Adesanya’s answer to an opponent refusing to threaten him off the kick and stance switch. With distance to work in, Adesanya brings out the heavy artillery and pounds in a left front kick to the body from his southpaw position (d, e). It is a shot that didn’t exist for him moments before. A front kick up that line from closed stance would only be a needling teep with the lead leg and not a full-hearted stomp to the guts from behind Adesanya’s centre of gravity.

Fig. 3

This in turn sets up a further trap shown in Figure 4: Adesanya’s question mark kick. Typically it is best to throw a question mark kick with the rear leg because it requires less remarkable flexibility and crucially, the kick is a misdirection technique. When kicking into the open side, a front kick or round kick to the body is a legitimate threat and it only takes a slight change of direction to score the question mark kick to the head. In a closed stance match up, the question mark kick often has to made to look like a low kick and then turned over drastically. There have been great lead leg question mark kickers of course—Glaube Feitosa being the most notable—but for most fighters, most of the time, rear leg question mark kicking is a better option.

Fig. 4

By performing the switch, Adesanya gives himself space to kick into the open side with his rear leg—resulting in a little more time for his opponent to react to the threat of the front kick, and a great deal more power when Adesanya turns his leg over. Finally, because he is now kicking into the open side, he has a great chance of ploughing through his opponent’s forearm and kicking it into their head anyway, rather than trying to negotiate kicking tightly over their lead shoulder on the closed side.

The Closed Stance Double Attack

Off the open stance position, Adesanya establishes the rear leg front kick and round kick to the body, along with the round kick or question mark kick to the head to create dilemmas for his opponent. He throws in the odd left straight to round out the classical Southpaw Double Attack, and adds more variety to his offence by consistently changing from one stance to the other and showing two sides of himself to the opponent throughout each round.

When Adesanya matches stances with his opponent—a closed stance match up—he offers another simple double attack. Figure 5 shows the first part of this. Adesanya stands with his rear hand forward of his guard, checking the line of the opponent’s jab (a). This squares his shoulders and coils his upper body to spring in with a powerful jab if he senses that the opponent has left his jabbing line free (b).

Fig. 5

This extended rear hand position will often draw the opponent into mirroring Adesanya and both fighters end up checking the path of their opponent’s jab. The second part of the double attack is the rear leg low kick. Because his shoulders and hips are more square than they would be ordinarily, Adesanya’s right low kick doesn’t have as much force on it as it could, but the squaring of the shoulders is the big tell on a low kick to begin with and he can get to the kick much faster. Sometimes he will throw it as a lead as the opponent is focusing on his jab and freeing their own jabbing hand, and other times he will check their jab and throw the kick to counter the opponent stepping onto the lead leg.

Fig. 6

The crux of this double threat is that Adesanya is fighting from a squared position. He has coiled up a powerful jab but lengthened the motion of the jab as a trade-off. And he has shortened and sped up the path of the low kick, at the expense of some power. This shaving down the length of strikes brings us onto a crucial element of Adesanya’s striking success: feinting.

The Art of Deception

Scarcely a moment of the fight goes by in which Israel Adesanya is not jiggling aggressively at his opponent and inviting them to do one of two things: buy the feint or ignore the feint. If they buy his feints he can exhaust them as they flinch at shadows, and land follow up techniques as they try to recover from missed reads.

Ignoring the feints is not the answer though. There are a myriad of ways to feint but Adesanya has mastered the type of feint that plays out identically to the first portion of a legitimate strike. This means that when an opponent attempts to ignore his feints, he can start letting the rest of his technique play out knowing that the opponent is going to let him get forty to fifty percent through the motion before they begin reacting.

Adesanya’s bread and butter feints are the shoulder feint and the hip feint. He will feign spins and step up kicks, but the shoulder feint and the hip feint are the most effective, require little commitment, and keep Adesanya in position to strike, retreat, counter or even sprawl.

The shoulder feint is a slight change of levels combined with a small forward step to push the lead shoulder towards the opponent. Figure 7 shows how Adesanya was able to apply this so well in kickboxing: a sport in which single shot jabbing from the outside is seldom seen. Hanging his lead hand low to begin (a), Adesanya steps forward and drops his weight slightly, coiling his lead hand (b). This portion of the movement is the shoulder feint but in actuality it is, of course, just the first 30% of jabbing for real.

Fig. 7

From the position in (b) Adesanya has committed nothing and can rebound and look to counter as his opponent returns, or draw his back foot up into his stance and do the same thing again. In Adesanya’s fight with Rob Wilkinson he was able to pump multiple shoulder feints in succession and move his feet to chase the skittish Wilkinson all the way to the fence. As opponents opted to ignore his feints or put on the earmuffs, Adesanya would snap the jab up from beneath them (c).

The hip feint is shown in Figure 8. Adesanya squares his shoulders and hips, bumps his back hip forward a little, and draws his back leg up to shorten his stance.

Fig. 8

The effect is that the opponent reacts to the threat of the rear leg kick. From a closed stance that could be the calf kick, and from an open stance that is the round kick and front kick to the body or the high kick. Just as with the shoulder feint, the hip feint is a technique that probes for a reaction but allows Adesanya to cover distance while also committing very little to his opponent.

A quirk of Adesanya’s game, which might be conscious or simply something that his body has learned without much thought, is the way that he throws his rear hand straight off this hip feint. Notice that in (b), as Adesanya hip feints he draws his left elbow back (a shortened version of throwing his arm back to counter balance on a kick) and Adesanya’s left fist is pulled in flush to his chest. This leads to a peculiar shot that you can see in Figure 9 below.

As Adesanya completes the hip feint (a) his left fist is in the centre of his chest, naturally flaring his left elbow out to the side. To capitalize on the feint, Adesanya drives off his left foot, which he was able to sneak closer to the opponent with the hip feint—extending the range he can lunge into (b, c). But as he throws his left straight his left elbow remains out to his side and he effectively backhands the punch in. It isn’t pretty punching form, and likely results in a loss of power, but it seems to sneak inside the parries of handsy opponents a bit easier.

Fig. 9

Figure 10 shows Adesanya putting it all together off the hip feint and it hinges around the position of his rear leg. He hip feints and sneaks his back leg up for the first time (a,b), before throwing the left straight (c,d). Adesanya keeps his left hand out and frames on his opponent, pushing them back as he draws his back leg up again (e). Keeping his left hand pushed into the opponent, Adesanya steps his lead leg forward again to make ground (f) and follows with a good body kick (g).

Fig. 10

Defensive Behaviours

In studying Israel Adesanya’s offensive game the expectation is to be dazzled by the combinations or the individual looks and set ups. As it turns out, Adesanya is more about good singles and doubles, and the occasional showings of razzle dazzle are not responsible for his incredible success. Instead it is the application of feinting and distancing between the basic attacks.

When looking at Adesanya’s defence it is again not one particular fancy technique or block or evasion but rather the disciplined use of correct distancing and ringcraft throughout a bout. He doesn’t let himself get caught on the fence easily, and crucially, he rarely retreats more than one step on a straight line.

Figure 11 shows the basic concept of circling out as Adesanya applies it. The first frame shows the two fighters feet set up at fighting range, but in reality this will come after a charge from one fighter and a retreat by the other: we are one step into a retreat and Adesanya needs to change direction to avoid running onto the fence. It is not even necessary to perform a big side step—if Adesanya can continue retreating but angle it out past his opponent’s lead foot and shoulder (b), he has cut off a lot of their offence and they will be forced to pivot, giving him time to escape.

Fig. 11

Adesanya has cultivated the ability to switch stances while retreating or circling out. This has two benefits: the first is that the opponent might run himself onto a counter that wasn’t there moments earlier. The second is that if Adesanya circles off and then re-engages, he will be doing it in a different stance, and the opponent—focused on his own thing—has a good chance of missing the switch and having to mentally play catch up.

Figure 12 shows Adesanya switching from a closed stance to an open stance matchup mid-retreat. As he shifts back and off to the left into southpaw (b) he lengthens the path of his opponent’s right hand. This is a very common southpaw tactic in MMA already: spiraling out from the opponent on the side of his power hand in hopes of getting him to overextend and countering across the top.

Fig. 12

The subtler move is switching from open stance to closed stance on the retreat as in Figure 13. The trick is to have the feet narrow in the stance from side-to-side so that as Adesanya swings his right foot back it can get outside opponent’s lead foot and shoulder. He pushes off his left foot in order to achieve this very slight angle, then he can begin circling out around the opponent as in Figure 11.

Fig. 13

Everyone has seen a mechanically perfect fighter who just cannot seem to score the wins as consistently as he should. There are a thousand reasons to win or lose a fight but perfect striking mechanics are too often considered “perfect technique.” Israel Adesanya brings to mind the great Willie Pep in many ways, because when you sit down and watch his fights it often looks as if he is making a lot of strange moves, or “getting away with” stylistic oddities because of his athleticism.

The truth, with Adesanya and with Pep, is that they do not have that Sugar Ray Robinson magic where if you took a photo during any exchange it might look as though the scene was posed for the cover of Ring Magazine. But they are brilliant technicians in something deeper: in the intangibles. They have the feints, they make the reads, they are close enough when they want to strike, and only seem closed enough when their opponent hopes to strike. They are built up from the principles of striking, not chiseled down to match the appearances in the textbooks.